History of Vietnam

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| History of Vietnam |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Vietnam |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Music |

| Sport |

The pre-history of Vietnam can be traced back to the arrival of Ancient East Eurasian hunter-gatherers that arrived at least 40,000 years ago. As part of the Initial Upper Paleolithic wave, the Hoabinhians, along with the Tianyuan man, are early members of the Ancient Basal East and Southeast Asian lineage deeply related to present-day East and Southeast Asians.[1][2] Human migration into Vietnam continued during the Neolithic period, characterized by movements of Southern East Asian populations that expanded from Southern China into Vietnam and South East Asia. See also Genetic history of East Asians. The earliest agricultural societies that cultivated millet and wet-rice emerged around 1700 BCE in the lowlands and river floodplains of Vietnam are associated with this Neolithic migration, indicated by the presences of major paternal lineages that are represented by East Eurasian-affiliated Y-haplogroups O, C2, and N.[3][4]

The Red River valley formed a natural geographic and economic unit, bounded to the north and west by mountains and jungles, to the east by the sea and to the south by the Red River Delta.[5] The need to have a single authority to prevent floods of the Red River, to cooperate in constructing hydraulic systems, trade exchange, and to repel invaders, led to the creation of the first legendary Vietnamese states approximately 2879 BC. Ongoing research from archaeologists has suggested that the Vietnamese Đông Sơn culture were traceable back to northern Vietnam, Guangxi and Laos around 1000 BC.[6][7][8]

Vietnam's long coastal and narrowed lands, rugged mountainous terrains, with two major deltas, were soon home to several different ancient cultures and civilizations. In the north, the Dong Son culture and its indigenous chiefdoms of Van Lang and Âu Lạc flourished by 500 BC. In Central Vietnam, the Sa Huỳnh culture of Austronesian Chamic peoples also thrived. Both were swept away by the Han dynasty expansion from the north, with the Han conquest of Nanyue bringing parts of Vietnam under Chinese rule in 111 BC. In 40 AD, the Trưng sisters led the first uprising of indigenous tribes and peoples against Chinese domination. The rebellion was defeated, but as the Han dynasty began to weaken by the late 2nd century AD and China started to descend into a state of turmoil, the indigenous peoples of Vietnam rose again and some became free. In 192 AD, the Cham of Central Vietnam revolted against the Chinese and subsequently formed the independent kingdom of Champa, while the Red River Delta saw a loosening of Chinese control. At that time, with the introduction of Buddhism and Hinduism by the 2nd century AD, Vietnam was the first place in Southeast Asia which shared influences of both Chinese and Indian cultures, and the rise of the first Indianized kingdoms Champa and Funan.

During these 1,000 years there were many uprisings against Chinese domination, and at certain periods Vietnam was independently governed under the Trưng Sisters, Early Lý, Khúc and Dương Đình Nghệ—although their triumphs and reigns were temporary. When Ngô Quyền (King of Vietnam, 938–944) restored sovereign power in the country with the victory at the battle of Bạch Đằng, the next millennium was advanced by the accomplishments of successive local dynasties: Ngô, Đinh, Early Lê, Lý, Trần, Hồ, Later Trần, Later Lê, Mạc, Revival Lê (Trịnh and Nguyễn), Tây Sơn, and Nguyễn. At various points during the imperial dynasties, Vietnam was ravaged and divided by civil wars and witnessed interventions by the Song, Yuan, Cham, Ming, Siamese, Qing, French, and Imperial Japan. Vietnam also conquered and colonized the Champa states and parts of Cambodia (today known as the Mekong Delta) between 1471 and 1760.

The Ming Empire conquered the Red River valley for a while before native Vietnamese regained control. The French Empire reduced Vietnam to a French dependency for nearly a century, followed by an occupation by the Japanese Empire. During the French period, widespread malnutrition and brutality from the 1880s until Japan invaded in 1940 created deep resentment that fueled resistance to post-World War II military-political efforts by France and the US.[9][10] Political upheaval and Communist insurrection put an end to the monarchy after World War II, and the country was proclaimed a republic in September 1945. After the fall of anti-communist state in Vietnam, it officially became a communist state in 1976.

Pre-historic period

[edit]

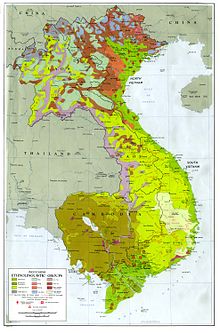

Vietnam is a multi-ethnic country on Mainland Southeast Asia and has great ethnolinguistic diversity. Vietnam's demography consists of 54 different ethnicities belonging to five major ethnolinguistic families: Austronesian, Austroasiatic, Hmong-Mien, Kra-Dai, Sino-Tibetan.[11] Among 54 groups, the majority ethnic group is the Austroasiatic-speaking Kinh, alone comprising 85.32% of total population. The rest is made up of 53 other ethnic groups. Vietnam's ethnic mosaic results from the peopling process in which various peoples came and settled the territory, leading to the modern state of Vietnam by many stages, often separated by thousands of years over a duration of tens of thousands of years. Vietnam's entire history, thus, is an embroidery of polyethnicity.[11]

Holocene Vietnam began during the Late Pleistocene period. Early anatomically modern human settlement in Mainland Southeast Asia dates back 65 to 10,5 kya (65,000 years ago).[11][12] Probably the foremost hunter-gatherers were the Hoabinhians, a large group that gradually settled across Southeast Asia, most likely akin to modern-day Munda people (Mundari-speaking people) and Malaysian Austroasiatics.[12] An analysis of individuals from the Con Co Ngua site in Thanh Hoa, Vietnam about 6.2 k cal BP, when restricted to Vietnamese comparisons, showed the closest distance to peoples from Mai Da Dieu, followed by present-day Vietnamese populations. Based on craniometric and dental nonmetric analysis, the Con Co Ngua individuals were phenotypically similar to Late Pleistocene Southeast Asians and modern Melanesians and Aboriginal Australians.[13]

Starting from the third millennium BCE, rice farming-based agriculture spread from southern East Asia into Mainland and Insular Southeast Asia. This technological spread was a result of the migration of East Asian agriculturalists that carried Ancient Southern East Asian ancestry. These Neolithic farmers took two routes: an inland route into Mainland Southeast Asia carried out by Austroasiatic speakers, and a maritime route that originated from Taiwan by Austronesian speakers.[14][15][16] In 2018, researchers conducted an genetic analysis on samples taken two ancient burial sites in Northern Vietnam, Mán Bạc and Núi Nấp, dating from 1,800 BCE and 100 BCE, respectively. The individuals at Mán Bạc show a mix of East Asian farmer and east Eurasian hunter-gatherer ancestry, with close genetic affinity for modern Austroasiatic groups like the Mlabri, the Nicobarese, and the Cambodians, while Nui Nap projects close to present-day Vietnamese and Dai.[17] A 2018 study by George van Driem et al. demonstrated that East Asian farmers intermixed with the native inhabitants and contrary to popular opinion, did not replace them. These farmers also shared ancestry with present-day Austroasiatic-speaking hill tribes themselves.[18]

The Cham people, who for over one thousand years settled in controlled and civilized present-day central and southern coastal Vietnam from around the 2nd century AD, are of Austronesian origin. The southernmost sector of modern Vietnam, the Mekong Delta and its surroundings were, until the 18th century, of integral yet shifting significance within the Austroasiatic Proto-Khmer – and Khmer principalities like Funan, Chenla, the Khmer Empire and the Khmer kingdom.[19][20][21]

Situated on the southeast edge of monsoon Asia, much of ancient Vietnam enjoyed a combination of high rainfall, humidity, heat, favorable winds, and fertile soil. These natural sources combined to generate an unusually prolific growth of rice and other plants and wildlife. This region's agricultural villages held well over 90 percent of the population. The high volume of rainy season water required villagers to concentrate their labor in managing floods, transplanting rice, and harvesting. These activities produced a cohesive village life with a religion in which one of the core values was the desire to live in harmony with nature and with other people. The way of life, centered in harmony, featured many enjoyable aspects that the people held beloved, typified by not needing many material things, the enjoyment of music and poetry, and living in harmony with nature.[22]

Fishing and hunting supplemented the main rice crop. Arrowheads and spears were dipped in poison to kill larger animals such as elephants. Betel nuts were widely chewed and the lower classes rarely wore clothing more substantial than a loincloth. Every spring, a fertility festival was held which featured huge parties and sexual abandon. Since around 2000 BC, stone hand tools and weapons improved extraordinarily in both quantity and variety. After this, Vietnam later became part of the Maritime Jade Road, which existed for 3,000 years between 2000 BC to 1000 AD.[23][24][25][26] Pottery reached a higher level of technique and decoration style. The early farming multilinguistic societies in Vietnam were mainly wet rice Oryza cultivators, which became the main staple of their diet. During the later stage of the first half of the 2nd millennium BC, the first appearance of bronze tools took place despite these tools still being rare. By about 1000 BC, bronze replaced stone for about 40 percent of edged tools and weapons, rising to about 60 percent. Here, there were not only bronze weapons, axes, and personal ornaments, but also sickles and other agriculture tools. Toward the closure of the Bronze Age, bronze accounts for more than 90 percent of tools and weapons, and there are exceptionally extravagant graves – the burial places of powerful chieftains – containing some hundreds of ritual and personal bronze artifacts, such as musical instruments, bucket-shaped ladles, and ornament daggers. After 1000 BC, the ancient peoples of Vietnam became skilled agriculturalists as they grew rice and kept buffaloes and pigs. They were also skilled fishermen and bold sailors, whose long dug-out canoes traversed the eastern sea.

Ancient period (c. 500–111 BC)

[edit]

Đông Sơn culture and the Legend of Hồng Bàng dynasty

[edit]

According to a Vietnamese legend which first appeared in the 14th century book Lĩnh nam chích quái, the tribal chief Lộc Tục (c. 2919 – 2794 BC) proclaimed himself as Kinh Dương Vương and founded the state of Xích Quỷ in 2879 BC, that marks the beginning of the Hồng Bàng dynastic period. However, modern Vietnamese historians assume, that statehood was only developed in the Red River Delta by the second half of 1st millennium BC. Kinh Dương Vương was succeeded by Sùng Lãm (c. 2825 BC – ?). The next royal dynasty produced 18 monarchs, known as the Hùng Kings, who renamed their country Văn Lang.[27] The administrative system includes offices like military chief (lạc tướng), paladin (lạc hầu) and mandarin (bố chính).[28] Great numbers of metal weapons and tools excavated at various Phung Nguyen culture sites in northern Indochina are associated with the beginning of the Copper Age in Southeast Asia.[29] Furthermore, the beginning of the Bronze Age has been verified for around 500 BC at Đông Sơn. Vietnamese historians usually attribute the Đông Sơn culture with the kingdoms of Văn Lang, Âu Lạc, and the Hồng Bàng dynasty. The local Lạc Việt community had developed a highly sophisticated industry of quality bronze production, processing and the manufacturing of tools, weapons and exquisite Bronze drums. Certainly of symbolic value, they were intended to be used for religious or ceremonial purposes. The craftsmen of these objects required refined skills in melting techniques, in the lost-wax casting technique and acquired master skills of composition and execution for the elaborate engravings.[30][31]

The Legend of Thánh Gióng tells of a youth, who leads the Văn Lang kingdom to victory against the Ân invaders from the north, saves the country and goes straight to heaven.[32][33] He wears iron armor, rides an armored horse and wields an iron sword.[34] The image implies a society of a certain sophistication in metallurgy as well as An Dương Vương's Legend of the Magic Crossbow, a weapon, that can fire thousands of bolts simultaneously, seems to hint at the extensive use of archery in warfare. The about 1,000 traditional craft villages of the Hồng River Delta near and around Hanoi represented throughout more than 2,000 years of Vietnamese history the national industrial and economic backbone.[35] Countless, mostly small family run manufacturers have over the centuries preserved their ethnic ideas by producing highly sophisticated goods, built temples and dedicated ceremonies and festivals in an unbroken culture of veneration for these legendary popular spirits.[36][37][38]

Âu Lạc kingdom (257–179 BC)

[edit]

By the 3rd century BC, another Viet group, the Âu Việt, emigrated from present-day southern China to the Hồng River delta and mixed with the indigenous Văn Lang population. In 257 BC, a new kingdom, Âu Lạc, emerged as the union of the Âu Việt and the Lạc Việt, with Thục Phán proclaiming himself "An Dương Vương" ("King An Dương"). Some modern Vietnamese believe that Thục Phán came upon the Âu Việt territory (modern-day northernmost Vietnam, western Guangdong, and southern Guangxi province, with its capital in what is today Cao Bằng Province).[39]

After assembling an army, he defeated and overthrew the eighteenth dynasty of the Hùng kings, around 258 BC. He then renamed his newly acquired state from Văn Lang to Âu Lạc and established the new capital at Phong Khê in the present-day Phú Thọ town in northern Vietnam, where he tried to build the Cổ Loa Citadel (Cổ Loa Thành), the spiral fortress approximately ten miles north of that new capital. However, records showed that espionage resulted in the downfall of An Dương Vương. At his capital, Cổ Loa, he built many concentric walls around the city for defensive purposes. These walls, together with skilled Âu Lạc archers, kept the capital safe from invaders.

Nanyue (180 BC–111 BC)

[edit]

In 207 BC, the former Qin general Zhao Tuo (Triệu Đà in Vietnamese) established an independent kingdom in the present-day Guangdong/Guangxi area of China's southern coast.[40] He proclaimed his new kingdom as Nam Việt (pinyin: Nanyue), to be ruled by the Zhao dynasty.[40] Zhao Tuo later appointed himself a commandant of central Guangdong, closing the borders and conquering neighboring districts and titled himself "King of Nanyue".[40] In 179 BC, he defeated King An Dương Vương and annexed Âu Lạc.[41]

The period has been given some controversial conclusions by Vietnamese historians, as some consider Zhao's rule as the starting point of the Chinese domination, since Zhao Tuo was a former Qin general; whereas others consider it still an era of Vietnamese independence as the Zhao family in Nanyue were assimilated into local culture.[42] They ruled independently of what then constituted the Han Empire. At one point, Zhao Tuo even declared himself Emperor, equal to the Han Emperor in the north.[40]

Chinese rule (111 BC–AD 938)

[edit]First Chinese domination (111 BC–AD 40)

[edit]

In 111 BC, the Han dynasty invaded Nanyue and established new territories, dividing Vietnam into Giao Chỉ (pinyin: Jiaozhi), now the Red River delta; Cửu Chân from modern-day Thanh Hóa to Hà Tĩnh; and Nhật Nam (pinyin: Rinan), from modern-day Quảng Bình to Huế. While governors and top officials were Chinese, the original Vietnamese nobles (Lạc Hầu, Lạc Tướng) from the Hồng Bàng period still managed in some of the highlands. During this period, Buddhism was introduced into Vietnam from India via the Maritime Silk Road, while Taoism and Confucianism spread to Vietnam through the Chinese rules.[43]

Trưng Sisters' rebellion (40–43)

[edit]In February AD 40, the Trưng Sisters led a successful revolt against Han Governor Su Ding (Vietnamese: Tô Định) and recaptured 65 states (including modern Guangxi). Trưng Trắc, angered by the killing of her husband by Su Dung, led the revolt together with her sister, Trưng Nhị. Trưng Trắc later became the Queen (Trưng Nữ Vương). In 43 AD, Emperor Guangwu of Han sent his famous general Ma Yuan (Vietnamese: Mã Viện) with a large army to quell the revolt. After a long, difficult campaign, Ma Yuan suppressed the uprising and the Trung Sisters committed suicide to avoid capture. To this day, the Trưng Sisters are revered in Vietnam as the national symbol of Vietnamese women.[44]

Second Chinese domination (43–544)

[edit]

Learning a lesson from the Trưng revolt, the Han and other successful Chinese dynasties took measures to eliminate the power of the Vietnamese nobles.[45] The Vietnamese elites were educated in Chinese culture and politics. A Giao Chỉ prefect, Shi Xie, ruled Vietnam as an autonomous warlord for forty years and was posthumously deified by later Vietnamese monarchs.[46][47] Shi Xie pledged loyalty to Eastern Wu of the Three Kingdoms era of China. The Eastern Wu was a formative period in Vietnamese history. According to Stephen O'Harrow, Shi Xie was essentially "the first Vietnamese".[48] Nearly 200 years passed before the Vietnamese attempted another revolt. In 248 a Yue woman, Triệu Thị Trinh with her brother Triệu Quốc Đạt, popularly known as Lady Triệu (Bà Triệu), led a revolt against the Wu dynasty. Once again, the uprising failed. Eastern Wu sent Lu Yin and 8,000 elite soldiers to suppress the rebels.[49] He managed to pacify the rebels with a combination of threats and persuasion. According to the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (Complete Annals of Đại Việt), Lady Triệu had long hair that reached her shoulders and rode into battle on an elephant. After several months of warfare she was defeated and committed suicide.[50]

Early Cham kingdoms (192–7th century)

[edit]

At the same time, in present-day Central Vietnam, there was a successful revolt of Cham nations in 192. Chinese dynasties called it Lin-Yi (Lin village; Vietnamese: Lâm Ấp). It later became a powerful kingdom, Champa, stretching from Quảng Bình to Phan Thiết (Bình Thuận). The Cham developed the first native writing system in Southeast Asia, oldest surviving literature of any Southeast Asian language, leading Buddhist, Hindu, and cultural expertise in the region.[51]

Funan kingdom (68–627)

[edit]In the early first century AD, on the lower Mekong, the first Indianized kingdom of Southeast Asia which the Chinese called them Funan emerged and became the great economic power in the region, its prime city Óc Eo attracted merchants and craftmen from China, India, and even Rome. The first ruler of Funan, Queen Liǔyè, got married with Kaundinya, a man from the west with a magic bow. Kaundinya then became the ruler of Funan. Funan is said to be the first Khmer state, or Austronesian, or multiethnic. According to Chinese annals, the last king of Funan, Rudravarman (r. 514–545) sent many embassies to China. Also according to Chinese annals, Funan might have been conquered by another kingdom called Zhenla around AD 627, ending the kingdom of Funan.[52]

Kingdom of Vạn Xuân (544–602)

[edit]In the period between the beginning of the Chinese Age of Fragmentation and the end of the Tang dynasty, several revolts against Chinese rule took place, such as those of Lý Bôn and his general and heir Triệu Quang Phục. All of them ultimately failed, yet most notable were those led by Lý Bôn and Triệu Quang Phục, who ruled the briefly independent Van Xuan kingdom for almost half a century, from 544 to 602, before Sui China reconquered the kingdom.[53]

Golden Age of Cham Civilization and wars with Angkor Empire (7th century–1203)

[edit]The Cham Lâm Ấp kingdom, with capital located in Simhapura, became prosperous through benefiting from the ancient maritime trade routes from the Middle East to China. The wealthy of Lâm Ấp attracted attention from the Chinese Empire. In 605, emperor Yang Guang of the Sui Empire ordered general Liu Fang, who had just reconquered and pacificed northern Vietnam, to invade Lâm Ấp. The kingdom was quickly overwhelmed by the invaders who pillaged and looted Cham sanctuaries. Despite that, king Sambhuvarman of Lâm Ấp (r. 572–629) quickly reasserted his independence, beginning the unified period of Champa in 629.[54]

From the 7th to the 10th centuries, the Cham controlled the trade in spices and silk between China, India, the Indonesian islands, and the Abbasid empire in Baghdad. They supplemented their income from the trade routes not only by exporting ivory and aloe, but also by engaging in piracy and raiding. This period of prosperity and cultural flourishing is often referred to as the golden age of Champa.

In 875, a new Mahayana Buddhist monarch named Indravarman II (r. 854–893) founded a new dynasty with Buddhism as state religion.[55] Indravarman II built a new capital city in Indrapura (modern-day Quảng Nam) and a large Buddhist temple in Dong Duong. The dynasty of Indravarman II continued to rule until the late 10th century, when a Vietnamese invasion in 982 murdered the ruling king Jaya Paramesvaravarman I (r. 972–982).[56] A Vietnamese usurper named Lưu Kế Tông took advance of unsettling situation and seized Indrapura in 983, declared himself the king of Champa in 986, disrupted the Cham kingdom. In Vijaya (present-day Binh Dinh) from the south, a new Hindu dynasty was founded in 989 and relocated Cham capital to Vijaya in 1000.[57]

Champa and the emerging Khmer Empire had waged war on each other for three centuries, from the 10th to 13th century. The Khmer first invaded Champa in Kauthara (Khanh Hoa) in 950.[58] In 1080, they attacked Vijaya and central Champa. The Cham under Harivarman IV launched counteroffensive against the Cambodian and plundered temples across east of the Mekong river. Tensions escalated during the next century. Suryavarman II of Khmer Empire invaded Champa in 1145 and 1149 after Cham ruler Indravarman refused to join with the Khmer campaign against the Vietnamese.[59] It was believed that Suryavarman II died during the war against Champa in 1150.[60] In 1177 Cham king Jaya Indravarman IV led a surprised attacked on Khmer capital Yasodharapura (Angkor) and defeated them at the Battle of Tonlé Sap.[61]

The new Cambodian ruler, Jayavarman VII, arose to power, repelled the Cham and began his conquest of Champa in 1190. He finally defeated the Cham in 1203 and put Champa under Khmer governance for 17 years. In 1220, as the Khmer voluntary withdraw from Champa, a Cham prince named Angsaraja proclaimed Jaya Paramesvaravarman II of Champa and restored Cham independence.[62]

Champa expanded its commerce to the Philippines in the 1200s. The History of Song notes that to the east of Champa through a two-day journey lay the country of Ma-i, at Mindoro, Philippines; while Pu-duan (Butuan) at Mindanao, need a seven-day journey, and there were mentions of Cham commercial activities in Butuan.[63] Butuan resented Champa commercial supremacy and their king, Rajah Kiling spearheaded a diplomatic rivalry for China trade against Champa hegemony.[64] Meanwhile, at the nation of the future Sultanate of Sulu which by then was still Hindu, there was a mass migration of men from Champa and they were locally known as Orang Dampuan, and they caused conflicts (which were then resolved) with the local Sulu people. They became the ancestors of the local Yakan people.[65][66]

Third Chinese domination (602–AD 905)

[edit]

During the Tang dynasty, Vietnam was called Annam until AD 866. With its capital around modern Bắc Ninh, Annam became a flourishing trading outpost, receiving goods from the southern seas. The Book of the Later Han recorded that in 166 the first envoy from the Roman Empire to China arrived by this route, and merchants were soon to follow. The 3rd-century Tales of Wei (Weilüe) mentioned a "water route" (the Red River) from Annam into what is now southern Yunnan. From there, goods were taken over land to the rest of China via the regions of modern Kunming and Chengdu. The capital of Annam, Tống Bình or Songping (today Hanoi) was a major urbanized settlement in the southwest region of Tang Empire. From 858 to 864, disturbances in Annan gave Nanzhao, a Yunnan kingdom, opportunity to intervene the region, provoking local tribes to revolt against the Chinese. The Yunnanese and their local allies launched the Siege of Songping in early 863, defeating the Chinese, and captured the capital in three years. In 866, Chinese jiedushi Gao Pian recaptured the city and drove out the Nanzhao army. He renamed the city to Daluocheng (大羅城, Đại La thành).

In 866, Annan was renamed Tĩnh Hải quân. Early in the 10th century, as China became politically fragmented, successive lords from the Khúc clan, followed by Dương Đình Nghệ, ruled Tĩnh Hải quân autonomously under the Tang title of Jiedushi (Vietnamese: Tiết Độ Sứ), (governor), but stopped short of proclaiming themselves kings.

Autonomous era (905–938)

[edit]

Since 905, Tĩnh Hải circuit had been ruled by local Vietnamese governors like an autonomous state.[67] Tĩnh Hải circuit had to paid tributes for Later Liang dynasty to exchange political protection.[68] In 923, the nearby Southern Han invaded Jinghai but was repelled by Vietnamese leader Dương Đình Nghệ.[69] In 938, the Chinese state Southern Han once again sent a fleet to subdue the Vietnamese. General Ngô Quyền (r. 938–944), Dương Đình Nghệ's son-in-law, defeated the Southern Han fleet at the Battle of Bạch Đằng (938). He then proclaimed himself King Ngô, established a monarchy government in Cổ Loa and effectively began the age of independence for Vietnam.

Dynastic period (939–1945)

[edit]

The basic nature of Vietnamese society changed little during the nearly 1,000 years between independence from China in the 10th century and the French conquest in the 19th century. Viet Nam, named Đại Việt (Great Viet) was a stable nation, but village autonomy was a key feature. Villages had a unified culture centered around harmony related to the religion of the spirits of nature and the peaceful nature of Buddhism. While the sovereign was the ultimate source of political authority, a saying was, "The Sovereign's Laws end at the village gate". The sovereign was the final dispenser of justice, law, and supreme commander-in-chief of the armed forces, as well as overseer of religious rituals. Administration was carried out by mandarins who were trained exactly like their Chinese counterparts (i.e. by rigorous study of Confucian texts). Overall, Vietnam remained very efficiently and stably governed except in times of war and dynastic breakdown. Its administrative system was probably far more advanced than that of any other Southeast Asian states and was more highly centralized and stably governed among Asian states. No serious challenge to the sovereign's authority ever arose, as titles of nobility were bestowed purely as honors and were not hereditary. Periodic land reforms broke up large estates and ensured that powerful landowners could not emerge. No religious/priestly class ever arose outside of the mandarins either. This stagnant absolutism ensured a stable, well-ordered society, but also resistance to social, cultural, or technological innovations. Reformers looked only to the past for inspiration.[70]

Literacy remained the province of the upper classes. Originally, only Chữ Hán was used to write, but by the 11th century, a set of derivative characters known as Chữ Nôm emerged that allowed native Vietnamese words to be written. However, it remained limited to poetry, literature, and practical texts like medicine while all state and official documents were written in Classical Chinese. Aside from some mining and fishing, agriculture was the primary activity of most Vietnamese, and economic development and trade were not promoted or encouraged by the state.[71]

First Dai Viet period

[edit]Ngô, Đinh, & Early Lê dynasties (938–1009)

[edit]

Ngô Quyền in 938 declared himself king, but died after only 6 years. His untimely death after a short reign resulted in a power struggle for the throne, resulting in the country's first major civil war, the upheaval of the Twelve Warlords (Loạn Thập Nhị Sứ Quân). The war lasted from 944 to 968, until the clan led by Đinh Bộ Lĩnh defeated the other warlords, unifying the country.[72] Đinh Bộ Lĩnh founded the Đinh dynasty and proclaimed himself Đinh Tiên Hoàng (Đinh the Majestic Emperor) and renamed the country from Tĩnh Hải quân to Đại Cồ Việt (literally "Great Viet"), with its capital in the city of Hoa Lư (modern-day Ninh Bình Province). The new emperor introduced strict penal codes to prevent chaos from happening again. He then tried to form alliances by granting the title of Queen to five women from the five most influential families. Đại La became the capital.

In 979, Emperor Đinh Tiên Hoàng and his crown prince Đinh Liễn were assassinated by Đỗ Thích, a government official, leaving his lone surviving son, the 6-year-old Đinh Toàn, to assume the throne. Taking advantage of the situation, the Song dynasty invaded Đại Cồ Việt. Facing such a grave threat to national independence, the commander of the armed forces, (Thập Đạo Tướng Quân) Lê Hoàn took the throne, replaced the house of Đinh and established the Early Lê dynasty. A capable military tactician, Lê Hoan realized the risks of engaging the mighty Song troops head on; thus, he tricked the invading army into Chi Lăng Pass, then ambushed and killed their commander, quickly ending the threat to his young nation in 981. The Song dynasty withdrew their troops and Lê Hoàn was referred to in his realm as Emperor Đại Hành (Đại Hành Hoàng Đế).[73] Emperor Lê Đại Hành was also the first Vietnamese monarch who began the southward expansion process against the kingdom of Champa.

Emperor Lê Đại Hành's death in 1005 resulted in infighting for the throne amongst his sons. The eventual winner, Lê Long Đĩnh, became the most notorious tyrant in Vietnamese history. He devised sadistic punishments of prisoners for his own entertainment and indulged in deviant sexual activities. Toward the end of his short life – he died at the age of 24 – Lê Long Đĩnh had become so ill, that he had to lie down when meeting with his officials in court.[74]

Lý dynasty, Trần dynasty & Hồ dynasty (1009–1407)

[edit]

When the king Lê Long Đĩnh died in 1009, a palace guard commander named Lý Công Uẩn was nominated by the court to take over the throne, and founded the Lý dynasty.[75] This event is regarded as the beginning of another golden era in Vietnamese history, with the following dynasties inheriting the Lý dynasty's prosperity and doing much to maintain and expand it. The way Lý Công Uẩn ascended to the throne was rather uncommon in Vietnamese history. As a high-ranking military commander residing in the capital, he had all opportunities to seize power during the tumultuous years after Emperor Lê Hoàn's death, yet preferring not to do so out of his sense of duty. He was in a way being "elected" by the court after some debate before a consensus was reached.[76]

The Lý monarchs are credited for laying down a concrete foundation for the nation of Vietnam. In 1010, Lý Công Uẩn issued the Edict on the Transfer of the Capital, moving the capital Đại Cồ Việt from Hoa Lư, a natural fortification surrounded by mountains and rivers, to the new capital in present-day Hanoi, Đại La, which was later renamed Thăng Long (Ascending Dragon) by Lý Công Uẩn, after allegedly seeing a dragon flying upwards when he arrived at the capital.[77][78] Moving the capital, Lý Công Uẩn thus departed from the militarily defensive mentality of his predecessors and envisioned a strong economy as the key to national survival. The third emperor of the dynasty, Lý Thánh Tông renamed the country "Đại Việt" (大越, Great Viet).[79] Successive Lý emperors continued to accomplish far-reaching feats: building a dike system to protect rice farms; founding the Quốc Tử Giám[80] the first noble university; and establishing court examination system to select capable commoners for government positions once every three years; organizing a new system of taxation;[81] establishing humane treatment of prisoners. Women were holding important roles in Lý society as the court ladies were in charge of tax collection. Neighboring Dali kingdom's Vajrayana Buddhism traditions also had influences on Vietnamese beliefs at the time. Lý kings adopted both Buddhism and Taoism as state religions.[82]

The Vietnamese during Lý dynasty had one major war with Song China, and a few invasive campaigns against neighboring Champa in the south.[83][84] The most notable conflict took place on Chinese territory Guangxi in late 1075. Upon learning that a Song invasion was imminent, the Vietnamese army under the command of Lý Thường Kiệt, and Tông Đản used amphibious operations to preemptively destroy three Song military installations at Yongzhou, Qinzhou, and Lianzhou in present-day Guangdong and Guangxi, and killed 100,000 Chinese.[85][86] The Song dynasty took revenge and invaded Đại Việt in 1076, but the Song troops were held back at the Battle of Như Nguyệt River commonly known as the Cầu river, now in Bắc Ninh province about 40 km from the current capital, Hanoi. Neither side was able to force a victory, so the Vietnamese court proposed a truce, which the Song emperor accepted.[87] Champa and the powerful Khmer Empire took advantage of Đại Việt's distraction with the Song to pillage Đại Việt's southern provinces. Together they invaded Đại Việt in 1128 and 1132.[88] Further invasions followed in the subsequent decades.[89]

Toward the declining Lý monarch's power in the late 12th century, the Trần clan from Nam Định eventually rise to power.[90] In 1224, powerful court minister Trần Thủ Độ forced the emperor Lý Huệ Tông to become a Buddhist monk and Lý Chiêu Hoàng, Huệ Tông's 8-year-old young daughter, to become ruler of the country.[91] Trần Thủ Độ then arranged the marriage of Chiêu Hoàng to his nephew Trần Cảnh and eventually had the throne transferred to Trần Cảnh, thus begun the Trần dynasty.[92]

Trần Thủ Độ viciously purged members of the Lý nobility; some Lý princes escaped to Korea, including Lý Long Tường. After the purge, the Trần emperors ruled the country in similar manner to the Lý kings. Noted Trần monarch accomplishments include the creation of a system of population records based at the village level, the compilation of a formal 30-volume history of Đại Việt (Đại Việt Sử Ký) by Lê Văn Hưu, and the rising in status of the Nôm script, a system of writing for Vietnamese language. The Trần dynasty also adopted a unique way to train new emperors: when a crown prince reached the age of 18, his predecessor would abdicate and turn the throne over to him, yet holding the title of Retired Emperor (Thái Thượng Hoàng), acting as a mentor to the new Emperor.

During the Trần dynasty, the armies of the Mongol Empire under Möngke Khan and Kublai Khan invaded Đại Việt in 1258, 1285, and 1287–88. Đại Việt repelled all attacks of the Yuan Mongols during the reign of Kublai Khan. Three Mongol armies said to have numbered from 300,000 to 500,000 men were defeated.[disputed – discuss] The key to Annam's successes was to avoid the Mongols' strength in open field battles and city sieges—the Trần court abandoned the capital and the cities. The Mongols were then countered decisively at their weak points, which were battles in swampy areas such as Chương Dương, Hàm Tử, Vạn Kiếp and on rivers such as Vân Đồn and Bạch Đằng. The Mongols also suffered from tropical diseases and loss of supplies to Trần army's raids. The Yuan-Trần war reached its climax when the retreating Yuan fleet was decimated at the Battle of Bạch Đằng (1288). The military architect behind Annam's victories was Commander Trần Quốc Tuấn, more popularly known as Trần Hưng Đạo. In order to avoid further disastrous campaigns, the Tran and Champa acknowledged Mongol supremacy. [citation needed]

In 1288, Venetian explorer Marco Polo visited Champa and Đại Việt. It was also during this period that the Vietnamese waged war against the southern kingdom of Champa, continuing the Vietnamese long history of southern expansion (known as Nam tiến) that had begun shortly after gaining independence in the 10th century. Often, they encountered strong resistance from the Chams. After the successful alliance with Champa during the Mongol invasion, king Trần Nhân Tông of Đại Việt gained two Champa provinces, located around present-day Huế, through the peaceful means of the political marriage of Princess Huyền Trân to Cham king Jaya Simhavarman III. Not long after the nuptials, the king died, and the princess returned to her northern home in order to avoid a Cham custom that would have required her to join her husband in death.[93] Champa was made a tributary state of Vietnam in 1312, but ten years later they regained independence and eventually waged a 30-years long war against the Vietnamese, in order to regain these lands and encouraged by the decline of Đại Việt in the course of the 14th century. Cham troops led by king Chế Bồng Nga (Cham: Po Binasuor or Che Bonguar, r. 1360–1390) killed king Trần Duệ Tông through a battle in Vijaya (1377).[94] Multiple Cham northward invasions from 1371 to 1390 put Vietnamese capital Thăng Long and Vietnamese economy in destruction.[95] However, in 1390 the Cham naval offensive against Hanoi was halted by the Vietnamese general Trần Khát Chân, whose soldiers made use of cannons.[96]

The wars with Champa and the Mongols left Đại Việt exhausted and bankrupt. The Trần family was in turn overthrown by one of its own court officials, Hồ Quý Ly. Hồ Quý Ly forced the last Trần emperor to abdicate and assumed the throne in 1400. He changed the country name to Đại Ngu and moved the capital to Tây Đô, Western Capital, now Thanh Hóa. Thăng Long was renamed Đông Đô, Eastern Capital. Although widely blamed for causing national disunity and losing the country later to the Ming Empire, Hồ Quý Ly's reign actually introduced a lot of progressive, ambitious reforms, including the addition of mathematics to the national examinations, the open critique of Confucian philosophy, the use of paper currency in place of coins, investment in building large warships and cannons, and land reform. He ceded the throne to his son, Hồ Hán Thương, in 1401 and assumed the title Thái Thượng Hoàng, in similar manner to the Trần kings.[97]

Champa from 1220 to 1471

[edit]After having been restored from Khmer domination in 1220, Champa continued to face another counter-power from the north. After their invasion of 982, the Vietnamese had been pushing war against Champa in 1020, 1044, and 1069, plundered Cham capital. In 1252 king Tran Thai Tong of the new dynasty of Dai Viet led an incursion into Cham territories, captured many Cham concubines and women. This might be the reason for the death of Jaya Paramesvaravarman II as he died in the same year. His younger brother, Prince Harideva of Sakanvijaya, was crowned as Jaya Indravarman VI (r. 1252–1257). The new king was however assassinated by his nephew in 1257, who became Indravarman V (r. 1257–1288).[98]

The new Mongol Yuan threat soon dragged two hostile kingdoms Champa and Dai Viet close together. The Yuan emperor Kublai demanded Cham submission in 1278 and 1280, both refused. In early 1283 Kublai sent a sea expedition led by Sogetu to invade Champa. The Cham retreated to the mountains, successfully waged a guerrilla resistance that bogged down the Mongols.[99] Sogetu was driven to the north, and later killed by joint Cham–Vietnamese forces in June 1285. Although having repulsed the Mongol yokes, the Cham king sent an ambassador to the great Khan in October 1285.[100] His successor, Jaya Simhavarman III (r. 1288–1307), married with a Vietnamese Queen (daughter of the ruling Vietnamese king) in 1306, and Dai Viet acquired two northern provinces.[101]

In 1307 the new Cham king Simhavarman IV (r. 1307–1312), set out to retake the two provinces to protest against the Vietnamese agreement but was defeated and taken as a prisoner. Champa thus became a Vietnamese vassal state.[102] The Cham revolted in 1318. In 1326 they managed to defeat the Vietnamese and reasserted independence.[103] Royal upheaval within the Cham court resumed until 1360, when a strong Cham king was enthroned, known as Po Binasuor (r. 1360–90). During his thirty-year reign, Champa gained its momentum peak. Po Binasuor annihilated the Vietnamese invaders in 1377, ransacked Hanoi in 1371, 1378, 1379, and 1383, nearly had united all Vietnam for the first time by the 1380s.[104] During a naval battle in early 1390, the Cham conqueror however was killed by Vietnamese firearm units, thus ending the short-lived rising period of the Cham kingdom.[105] During the next decades, Champa returned to its status quo of peace. After much warfare and dismal conflicts, king Indravarman VI (r. 1400–41) reestablished relations with the second kingdom of Dai Viet's ruler Le Loi in 1428.[105]

The Islamization of Champa began in the 8th century to 11th century, being faster proselytized during the 14th and 15th centuries. Ibn Battuta during his visit to Champa in 1340, described a princess who met him, spoke in Turkish, was literate in Arabic, and wrote out the bismillah in the presence of the visitor.[103] Islam further got more popular in Cham society after the fall of Champa in 1471.[106] After the death of Indravarman VI, succession disputes escalated into civil war between Cham princes, weakening the kingdom. The Vietnamese took advantage, raided Vijaya in 1446. In 1471 Dai Viet king Le Thanh Tong conquered Champa, killed 60,000 people, and took away 30,000 prisoners included the Cham king and the royal family. Champa was reduced to the rump state of Panduranga, which persisted to exist until being fully absorbed in 1832 by the Vietnamese Empire.[106]

Fourth Chinese domination (1407–1427)

[edit]

In 1407, under the pretext of helping to restore the Trần monarchs, Chinese Ming troops invaded Đại Ngu and captured Hồ Quý Ly and Hồ Hán Thương.[107] The Hồ family came to an end after only 7 years in power. The Ming occupying force annexed Đại Ngu into the Ming Empire after claiming that there was no heir to the Trần throne. Vietnam, weakened by dynastic feuds and the wars with Champa, quickly succumbed. The Ming conquest was harsh. Vietnam was annexed directly as a province of China, the old policy of cultural assimilation again imposed forcibly, and the country was ruthlessly exploited.[108] However, by this time, Vietnamese nationalism had reached a point where attempts to sinicize them could only strengthen further resistance. Almost immediately, Trần loyalists started a resistance war. The resistance, under the leadership of Trần Quý Khoáng at first gained some advances, yet as Trần Quý Khoáng executed two top commanders out of suspicion, a rift widened within his ranks and resulted in his defeat in 1413.[109]

Restored Dai Viet period (1428–1527)

[edit]Later Lê dynasty – primitive period (1427–1527)

[edit]

In 1418, Lê Lợi was the son of a wealthy aristocrat in Thanh Hóa, led the Lam Sơn uprising against the Ming from his base of Lam Sơn (Thanh Hóa province). Overcoming many early setbacks and with strategic advice from Nguyễn Trãi, Lê Lợi's movement finally gathered momentum. In September 1426, the Lam Sơn rebellion marched northward, ultimately defeated the Ming army in the Battle of Tốt Động – Chúc Động in south of Hanoi by using cannons.[110] Then Lê Lợi's forces launched a siege at Đông Quan (now Hanoi), the capital of the Ming occupation. The Xuande Emperor of Ming China responded by sent two reinforcement forces of 122,000 men, but Lê Lợi staged an ambush and killed the Ming commander Liu Shan in Chi Lăng.[109] Ming troops at Đông Quan surrendered. The Lam Sơn rebels defeated 200,000 Ming soldiers.[111]

In 1428, Lê Lợi reestablished the independent of Vietnam under his Lê dynasty. Lê Lợi renamed the country back to Đại Việt and moved the capital back to Thăng Long, renamed it Đông Kinh.

The Lê kings carried out land reforms to revitalize the economy after the war. Unlike the Lý and Trần kings, who were more influenced by Buddhism, the Lê kings leaned toward Confucianism. A comprehensive set of laws, the Hồng Đức code was introduced in 1483 with some strong Confucian elements, yet also included some progressive rules, such as the rights of women. Art and architecture during the Lê dynasty also became more influenced by Chinese styles than during previous Lý and Trần dynasties. The Lê dynasty commissioned the drawing of national maps and had Ngô Sĩ Liên continue the task of writing Đại Việt's history up to the time of Lê Lợi.

Overpopulation and land shortages stimulated a Vietnamese expansion south. In 1471, Dai Viet troops led by king Lê Thánh Tông invaded Champa and captured its capital Vijaya. This event effectively ended Champa as a powerful kingdom, although some smaller surviving Cham states lasted for a few centuries more. It initiated the dispersal of the Cham people across Southeast Asia. With the kingdom of Champa mostly destroyed and the Cham people exiled or suppressed, Vietnamese colonization of what is now central Vietnam proceeded without substantial resistance. However, despite becoming greatly outnumbered by Vietnamese settlers and the integration of formerly Cham territory into the Vietnamese nation, the majority of Cham people nevertheless remained in Vietnam and they are now considered one of the key minorities in modern Vietnam. Vietnamese armies also raided the Mekong Delta, which the decaying Khmer Empire could no longer defend. The city of Huế, founded in 1600 lies close to where the Champa capital of Indrapura once stood. In 1479, Lê Thánh Tông also campaigned against Laos in the Vietnamese–Lao War and captured its capital Luang Prabang, in which later the city was totally ransacked and destroyed by the Vietnamese. He made further incursions westwards into the Irrawaddy River region in modern-day Burma before withdrawing. After the death of Lê Thánh Tông, Dai Viet fell into a swift decline (1497–1527), with 6 rulers in within 30 years of failing economy, natural disasters and rebellions raged through the country. European traders and missionaries, reaching Vietnam in the midst of the Age of Discovery, were at first Portuguese, and started spreading Christianity since 1533.[112]

Decentralized period (1527–1802)

[edit]Mạc & Later Lê dynasties – restored period (1527–1788)

[edit]

The Lê dynasty was overthrown by its general named Mạc Đăng Dung in 1527. He killed the Lê emperor and proclaimed himself emperor, starting the Mạc dynasty. After defeating many revolutions for two years, Mạc Đăng Dung adopted the Trần dynasty's practice and ceded the throne to his son, Mạc Đăng Doanh, and he became Thái Thượng Hoàng.

Meanwhile, Nguyễn Kim, a former official in the Lê court, revolted against the Mạc and helped king Lê Trang Tông restore the Lê court in the Thanh Hóa area. Thus a civil war began between the Northern Court (Mạc) and the Southern Court (Restored Lê). Nguyễn Kim's side controlled the southern part of Annam (from Thanhhoa to the south), leaving the north (including Đông Kinh-Hanoi) under Mạc control.[113] When Nguyễn Kim was assassinated in 1545, military power fell into the hands of his son-in-law, Trịnh Kiểm. In 1558, Nguyễn Kim's son, Nguyễn Hoàng, suspecting that Trịnh Kiểm might kill him as he had done to his brother to secure power, asked to be governor of the far south provinces around present-day Quảng Bình to Bình Định. Hoàng pretended to be insane, so Kiểm was fooled into thinking that sending Hoàng south was a good move as Hoàng would be quickly killed in the lawless border regions.[114] However, Hoàng governed the south effectively while Trịnh Kiểm, and then his son Trịnh Tùng, carried on the war against the Mạc. Nguyễn Hoàng sent money and soldiers north to help the war but gradually he became more and more independent, transforming their realm's economic fortunes by turning it into an international trading post.[114]

The civil war between the Lê-Trịnh and Mạc dynasties ended in 1592, when the army of Trịnh Tùng conquered Hanoi and executed king Mạc Mậu Hợp. Survivors of the Mạc royal family fled to the northern mountains in the province of Cao Bằng and continued to rule there until 1677 when Trịnh Tạc conquered this last Mạc territory. The Lê monarchs, ever since Nguyễn Kim's restoration, only acted as figureheads. After the fall of the Mạc dynasty, all real power in the north belonged to the Trịnh lords. Meanwhile, the Ming court reluctantly decided on a military intervention into the Vietnamese civil war, but Mạc Đăng Dung offered ritual submission to the Ming Empire, which was accepted. Since the late 16th century, trades and contacts between Japan and Vietnam increased as they established relationship in 1591.[115] The Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan and governor Nguyễn Hoàng of Quảng Nam exchanged total 34 letters from 1589 to 1612, and a Japanese town was established in the city of Hội An in 1604.[115]

Trịnh & Nguyễn lords (1627-1777)

[edit]

In the year 1600, Nguyễn Hoàng also declared himself Lord (officially "Vương", popularly "Chúa") and refused to send more money or soldiers to help the Trịnh. He also moved his capital to Phú Xuân, modern-day Huế. Nguyễn Hoàng died in 1613 after having ruled the south for 55 years. He was succeeded by his 6th son, Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên, who likewise refused to acknowledge the power of the Trịnh, yet still pledged allegiance to the Lê monarch.[116]

Trịnh Tráng succeeded Trịnh Tùng, his father, upon his death in 1623. Tráng ordered Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên to submit to his authority. The order was refused twice. In 1627, Trịnh Tráng sent 150,000 troops southward in an unsuccessful military campaign. The Trịnh were much stronger, with a larger population, economy and army, but they were unable to vanquish the Nguyễn, who had built two defensive stone walls and invested in Portuguese artillery.

The Trịnh–Nguyễn War lasted from 1627 until 1672. The Trịnh army staged at least seven offensives, all of which failed to capture Phú Xuân. For a time, starting in 1651, the Nguyễn themselves went on the offensive and attacked parts of Trịnh territory. However, the Trịnh, under a new leader, Trịnh Tạc, forced the Nguyễn back by 1655. After one last offensive in 1672, Trịnh Tạc agreed to a truce with the Nguyễn Lord Nguyễn Phúc Tần. The country was effectively divided in two.

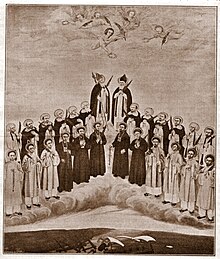

Advent of Europeans & southward expansion

[edit]The West's exposure to Annam and Annamese exposure to Westerners dated back to 166 AD[117] with the arrival of merchants from the Roman Empire, to 1292 with the visit of Marco Polo, and the early 16th century with the arrival of Portuguese in 1516 and other European traders and missionaries.[117] Alexandre de Rhodes, a Jesuit priest from the Papal States, improved on earlier work by Portuguese missionaries and developed the Vietnamese romanized alphabet chữ Quốc ngữ in Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum in 1651.[118] Jesuits in the 17th century established a firm foundation of Christianity in both domains of Đàng Ngoài (Tonkin) and Đàng Trong (Cochinchina).[119] Various European efforts to establish trading posts in Vietnam failed, but missionaries were allowed to operate for some time until the mandarins began concluding that Christianity (which had succeeded in converting up to a tenth of the population by 1700) was a threat to the Confucian social order since it condemned ancestor worship as idolatry. Vietnamese authorities' attitudes to Europeans and Christianity hardened as they began to increasingly see it as a way of undermining society.

Between 1627 and 1775, two powerful families had partitioned the country: the Nguyễn lords ruled the South and the Trịnh lords ruled the North. The Trịnh–Nguyễn War gave European traders the opportunities to support each side with weapons and technology: the Portuguese assisted the Nguyễn in the South while the Dutch helped the Trịnh in the North. The Trịnh and the Nguyễn maintained a relative peace for the next hundred years, during which both sides made significant accomplishments. The Trịnh created centralized government offices in charge of state budget and producing currency, unified the weight units into a decimal system, established printing shops to reduce the need to import printed materials from China, opened a military academy, and compiled history books.

Meanwhile, the Nguyễn lords continued the southward expansion by the conquest of the remaining Cham land. Việt settlers also arrived in the sparsely populated area known as "Water Chenla", which was the lower Mekong Delta portion of the former Khmer Empire. Between the mid-17th century to mid-18th century, as the former Khmer Empire was weakened by internal strife and Siamese invasions, the Nguyễn Lords used various means, political marriage, diplomatic pressure, political and military favors, to gain the area around present-day Saigon and the Mekong Delta. The Nguyễn army at times also clashed with the Siamese army to establish influence over the former Khmer Empire.

Tây Sơn dynasty (1778–1802)

[edit]

In 1771, the Tây Sơn revolution broke out in Quy Nhon, which was under the control of the Nguyễn lord.[120] The leaders of this revolution were three brothers named Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Lữ, and Nguyễn Huệ, not related to the Nguyễn lord's family. In 1773, Tây Sơn rebels took Quy Nhon as the capital of the revolution. Tây Sơn brothers' forces attracted many poor peasants, workers, Christians, ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands and Cham people who had been oppressed by the Nguyễn Lord for a long time,[121] and also attracted to ethnic Chinese merchant class, who hope the Tây Sơn revolt will spare down the heavy tax policy of the Nguyễn Lord, however their contributions later were limited due to Tây Sơn's nationalist anti-Chinese sentiment.[120] By 1776, the Tây Sơn had occupied all of the Nguyễn Lord's land and killed almost the entire royal family. The surviving prince Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (often called Nguyễn Ánh) fled to Siam, and obtained military support from the Siamese king. Nguyễn Ánh came back with 50,000 Siamese troops to regain power, but was defeated at the Battle of Rạch Gầm–Xoài Mút and almost killed. Nguyễn Ánh fled Vietnam, but he did not give up.[122]

The Tây Sơn army commanded by Nguyễn Huệ marched north in 1786 to fight the Trịnh Lord, Trịnh Khải. The Trịnh army failed and Trịnh Khải committed suicide. The Tây Sơn army captured the capital in less than two months. The last Lê emperor, Lê Chiêu Thống, fled to Qing China and petitioned the Qianlong Emperor in 1788 for help. The Qianlong Emperor supplied Lê Chiêu Thống with a massive army of around 200,000 troops to regain his throne from the usurper. In December 1788, Nguyễn Huệ–the third Tây Sơn brother–proclaimed himself Emperor Quang Trung and defeated the Qing troops with 100,000 men in a surprise 7 day campaign during the lunar new year (Tết). There was even a rumor saying that Quang Trung had also planned to conquer China, although it was unclear. During his reign, Quang Trung envisioned many reforms but died by unknown reason on the way march south in 1792, at the age of 40. During the reign of Emperor Quang Trung, Đại Việt was in fact divided into three political entities.[123] The Tây Sơn leader, Nguyễn Nhạc, ruled the centre of the country from his capital Qui Nhơn. Emperor Quang Trung ruled the north from the capital Phú Xuân Huế. In the South. He officially funded and trained the Pirates of the South China Coast – one of the most strongest and feared pirate army in the world late 18th century–early 19th century.[124] Nguyễn Ánh, assisted by many talented recruits from the South, captured Gia Định (present-day Saigon) in 1788 and established a strong base for his force.[125]

In 1784, during the conflict between Nguyễn Ánh, the surviving heir of the Nguyễn lords, and the Tây Sơn dynasty, a French Roman Catholic prelate, Pigneaux de Behaine, sailed to France to seek military backing for Nguyễn Ánh. At Louis XVI's court, Pigneaux brokered the Little Treaty of Versailles which promised French military aid in exchange for Vietnamese concessions. However, because of the French Revolution, Pigneaux's plan failed to materialize. He went to the French territory of Pondichéry (India), and secured two ships, a regiment of Indian troops, and a handful of volunteers and returned to Vietnam in 1788. One of Pigneaux's volunteers, Jean-Marie Dayot, reorganized Nguyễn Ánh's navy along European lines and defeated the Tây Sơn at Quy Nhon in 1792. A few years later, Nguyễn Ánh's forces captured Saigon, where Pigneaux died in 1799. Another volunteer, Victor Olivier de Puymanel would later build the Gia Định fort in central Saigon. [citation needed]

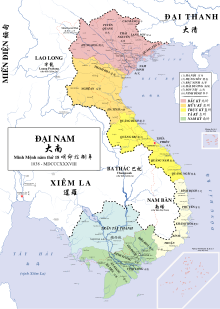

After Quang Trung's death in September 1792, the Tây Sơn court became unstable as the remaining brothers fought against each other and against the people who were loyal to Nguyễn Huệ's young son. Quang Trung's 10-years-old son Nguyễn Quang Toản succeeded the throne, became Cảnh Thịnh Emperor, the third ruler of the Tây Sơn dynasty. In the South, lord Nguyễn Ánh and the Nguyễn royalists were assisted with French, Chinese, Siamese and Christian supports, sailed north in 1799, capturing Tây Sơn's stronghold Quy Nhon.[127] In 1801, his force took Phú Xuân, the Tây Sơn capital. Nguyễn Ánh finally won the war in 1802, when he sieged Thăng Long (Hanoi) and executed Nguyễn Quang Toản, along with many Tây Sơn royals, generals and officials. Nguyễn Ánh ascended the throne and called himself Emperor Gia Long. Gia is for Gia Định, the old name of Saigon; Long is for Thăng Long, the old name of Hanoi. Hence Gia Long implied the unification of the country. The Nguyễn dynasty lasted until Bảo Đại's abdication in 1945. As China for centuries had referred to Đại Việt as Annam, Gia Long asked the Manchu Qing emperor to rename the country, from Annam to Nam Việt. To prevent any confusion of Gia Long's kingdom with Triệu Đà's ancient kingdom, the Manchu emperor reversed the order of the two words to Việt Nam. The name Vietnam is thus known to be used since Emperor Gia Long's reign. Recently historians have found that this name had existed in older books in which Vietnamese referred to their country as Vietnam.[citation needed][when?]

The Period of Division with its many tragedies and dramatic historical developments inspired many poets and gave rise to some Vietnamese masterpieces in verse, including the epic poem The Tale of Kiều (Truyện Kiều) by Nguyễn Du, Song of a Soldier's Wife (Chinh Phụ Ngâm) by Đặng Trần Côn and Đoàn Thị Điểm, and a collection of satirical, erotically charged poems by a female poet, Hồ Xuân Hương.

Unified Vietnam period (1802–1862)

[edit]Nguyễn dynasty (1802–1945)

[edit]

After Nguyễn Ánh established the Nguyễn dynasty in 1802, he tolerated Catholicism and employed some Europeans in his court as advisors. His successors were more conservative Confucians and resisted Westernization. The next Nguyễn emperors, Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị, and Tự Đức brutally suppressed Catholicism and pursued a 'closed door' policy, perceiving the Westerners as a threat, following events such as the Lê Văn Khôi revolt when a French missionary, Fr. Joseph Marchand, was accused of encouraging local Catholics to revolt in an attempt to install a Catholic emperor. Catholics, both Vietnamese and foreign-born, were persecuted in retaliation. Trade with the West slowed during this period. There were frequent uprisings against the Nguyễns, with hundreds of such events being recorded in the annals. These acts were soon being used as excuses for France to invade Vietnam. The early Nguyễn dynasty had engaged in many of the constructive activities of its predecessors, building roads, digging canals, issuing a legal code, holding examinations, sponsoring care facilities for the sick, compiling maps and history books, and exerting influence over Cambodia and Laos. [citation needed]

Relations with China

[edit]According to a 2018 study in the Journal of Conflict Resolution covering Vietnam-China relations from 1365 to 1841, the relations could be characterized as a "hierarchic tributary system".[128] The study found that "the Vietnamese court explicitly recognized its unequal status in its relations with China through a number of institutions and norms. Vietnamese rulers also displayed very little military attention to their relations with China. Rather, Vietnamese leaders were clearly more concerned with quelling chronic domestic instability and managing relations with kingdoms to their south and west."[128]

French conquest

[edit]The French colonial empire was heavily involved in Vietnam in the 19th century; often French intervention was undertaken in order to protect the work of the Paris Foreign Missions Society in the country. In response to many incidents in which Catholic missionaries were persecuted, harassed and in some cases executed, and also to expand French influence in Asia, Napoleon III of France ordered Charles Rigault de Genouilly with 14 French gunships to attack the port of Đà Nẵng (Tourane) in 1858. The attack caused significant damage, yet failed to gain any foothold, in the process being afflicted by the humidity and tropical diseases. De Genouilly decided to sail south and captured the poorly defended city of Gia Định (present-day Ho Chi Minh City). From 1859 during the Siege of Saigon to 1867, French troops expanded their control over all six provinces on the Mekong delta and formed a colony known as Cochinchina.

A few years later, French troops landed in northern Vietnam (which they called Tonkin) and captured Hà Nội twice in 1873 and 1882. The French managed to keep their grip on Tonkin although, twice, their top commanders Francis Garnier and Henri Rivière, were ambushed and killed fighting pirates of the Black Flag Army hired by the mandarins. The Nguyễn dynasty surrendered to France via the Treaty of Huế (1883), marking the colonial era (1883–1954) in the history of Vietnam. France assumed control over the whole of Vietnam after the Tonkin Campaign (1883–1886). French Indochina was formed in October 1887 from Annam (Trung Kỳ, central Vietnam), Tonkin (Bắc Kỳ, northern Vietnam) and Cochinchina (Nam Kỳ, southern Vietnam), with Cambodia and Laos added in 1893. Within French Indochina, Cochinchina had the status of a colony, Annam was nominally a protectorate where the Nguyễn dynasty still ruled, and Tonkin had a French governor with local governments run by Vietnamese officials. [citation needed]

French colonial period (1862–1945)

[edit]French colonial conquest of Vietnam (1858–1897)

[edit]

After Vietnam lost Gia Định, the island of Poulo Condor, and three southern provinces to France with the Treaty of Saigon between the Nguyễn dynasty and France in 1862, many resistance movements in the south refused to recognize the treaty and continued to fight the French, some led by former court officers, such as Trương Định, some by farmers and other rural people, such as Nguyễn Trung Trực, who sank the French gunship L'Esperance using guerilla tactics. In the north, most movements were led by former court officers, and fighters were from the rural population. Sentiment against the invasion ran deep in the countryside—well over 90 percent of the population—because the French seized and exported most of the rice, creating widespread malnutrition from the 1880s onward. And, an ancient tradition existed of repelling all invaders. These were two reasons that the vast majority opposed the French invasion.[129][130]

Some of the resistance movements lasted decades, with Phan Đình Phùng fighting in central Vietnam until 1895, and in the northern mountains, former bandit leader Hoàng Hoa Thám fought until 1911. Even the teenage Nguyễn Emperor Hàm Nghi left the Imperial Palace of Huế in 1885 with regent Tôn Thất Thuyết and started the Cần Vương ("Save the King") movement, trying to rally the people to resist the French. He was captured in 1888 and exiled to French Algeria.

During this period, many Catholic converts collaborated with the French. This gave Catholics “an aura of subversion and treachery,” stated Neil Sheehan in A Bright Shining Lie, and people who sided with the French were called “country sellers.” By siding with the invaders, Catholics gained “the impression of being a foreign body,” said cultural expert Huu Ngoc. Catholics assisted, Jean Chesneaux wrote, in “breaking the isolation of the French troops.” Likewise, Paul Isoart reported: “The insurrection in Annam was liquidated thanks to the information the French received from the Vietnamese Catholics.” Some information was obtained in confessionals. Vicar Paul Francois Puginier of Ha Noi sent regular reports to secular authorities, including information about unrest and possible uprisings.[131] In contrast, in Cambodia, which is also a part of French-Cochinchina, like Vietnam, the French restored the Kingdom of Cambodia as a Protectorate from its previous invader, Thailand,[132] which occupied and destroyed Cambodia. Fulfilling a past promise by Spanish-Philippines to restore Cambodia,[133] which the French-Vietnamese instead fulfilled,[134] and both peoples being mostly Catholics.

The invaders seized many farmlands and gave them to Frenchmen and collaborators, who were usually Catholics. By 1898, these seizures created a large class of poor people with little or no land, and a small class of wealthy landowners dependent on the French. In 1905, a Frenchman observed that “Traditional Annamite society, so well organized to satisfy the needs of the people has, in the final analysis, been destroyed by us.” This split in society lasted into the war in the 1960s.[135]

Guerrillas of the Cần Vương movement killed around a third of Vietnam's Christian population during the resistance war.[136] Decades later, two more Nguyễn kings, Thành Thái and Duy Tân were also exiled to Africa for having anti-French tendencies. The former was deposed on the pretext of insanity and Duy Tân was caught in a conspiracy with the mandarin Trần Cao Vân trying to start an uprising. However, lack of modern weapons and equipment prevented these resistance movements from being able to engage the French in open combat. The various anti-French started by mandarins were carried out with the primary goal of restoring the old feudal society. However, by 1900 a new generation of Vietnamese were coming of age who had never lived in precolonial Vietnam. These young activists were as eager as their grandparents to see independence restored, but they realized that returning to the feudal order was not feasible and that modern technology and governmental systems were needed. Having been exposed to Western philosophy, they aimed to establish a republic upon independence, departing from the royalist sentiments of the Cần Vương movements. Some of them set up Vietnamese independence societies in Japan, which many viewed as a model society (i.e. an Asian nation that had modernized, but retained its own culture and institutions). [citation needed]

French Indochina and Vietnamese nationalist movements (1897–1945)

[edit]

There emerged two parallel movements of modernization. The first was the Đông Du ("Travel to the East") Movement started in 1905 by Phan Bội Châu. Châu's plan was to send Vietnamese students to Japan to learn modern skills, so that in the future they could lead a successful armed revolt against the French. With Prince Cường Để, he started two organizations in Japan: Duy Tân Hội and Việt Nam Công Hiến Hội. Due to French diplomatic pressure, Japan later deported Châu. Phan Châu Trinh, who favored a peaceful, non-violent struggle to gain independence, led a second movement, Duy Tân (Modernization), which stressed education for the masses, modernizing the country, fostering understanding and tolerance between the French and the Vietnamese, and peaceful transitions of power. The early part of the 20th century saw the growing in status of the Romanized Quốc Ngữ alphabet for the Vietnamese language. Vietnamese patriots realized the potential of Quốc Ngữ as a useful tool to quickly reduce illiteracy and to educate the masses. The traditional Chinese scripts or the Nôm script were seen as too cumbersome and too difficult to learn. The use of prose in literature also became popular with the appearance of many novels; most famous were those from the Tự Lực Văn Đoàn literary circle. [citation needed]

As the French suppressed both movements, and after witnessing revolutionaries in action in China and Russia, Vietnamese revolutionaries began to turn to more radical paths. Phan Bội Châu created the Việt Nam Quang Phục Hội in Guangzhou, planning armed resistance against the French. In 1925, French agents captured him in Shanghai and spirited him to Vietnam. Due to his popularity, Châu was spared from execution and placed under house arrest until his death in 1940. In 1927, the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (Vietnamese Nationalist Party), modeled after the Kuomintang in China, was founded, and the party launched the armed Yên Bái mutiny in 1930 in Tonkin which resulted in its chairman, Nguyễn Thái Học and many other leaders captured and executed by the guillotine. [137][138]

Marxism was also introduced into Vietnam with the emergence of three separate Communist parties; the Indochinese Communist Party, Annamese Communist Party and the Indochinese Communist Union, joined later by a Trotskyist movement led by Tạ Thu Thâu. In 1930, the Communist International (Comintern) sent Nguyễn Ái Quốc to Hong Kong to coordinate the unification of the parties into the Vietnamese Communist Party (CPV) with Trần Phú as the first Secretary General. Later the party changed its name to the Indochinese Communist Party as the Comintern, under Stalin, did not favor nationalistic sentiments. Being a leftist revolutionary living in France since 1911, Nguyễn Ái Quốc participated in founding the French Communist Party and in 1924 traveled to the Soviet Union to join the Comintern. Through the late 1920s, he acted as a Comintern agent to help build Communist movements in Southeast Asia. During the 1930s, the CPV was nearly wiped out under French suppression with the execution of top leaders such as Phú, Lê Hồng Phong, and Nguyễn Văn Cừ. [citation needed]

Second World War and Independence

[edit]During World War II, Japan invaded Indochina in 1940, keeping the Vichy French colonial administration in place as a puppet. In 1941 Nguyễn Sinh Cung, now known as Hồ Chí Minh, arrived in northern Vietnam to form the Việt Minh Front, and it was supposed to be an umbrella group for all parties fighting for Vietnam's independence, but was dominated by the Communist Party. The Việt Minh had a modest armed force and during the war worked with the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to collect intelligence on the Japanese.

On March 9, 1945, the Japanese removed Vichy France's control of Indochina, and created the short-lived Empire of Vietnam with Bảo Đại as the emperor. A famine broke out in 1944–45, leaving from 600,000 to 2,000,000 dead.[139]

Japan's defeat by the World War II Allies created a power vacuum for Vietnamese nationalists of all parties to seize power in August 1945, forcing Emperor Bảo Đại to abdicate and ending the Nguyễn dynasty. On September 2, 1945, Hồ Chí Minh read the Proclamation of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in Ba Đình flower garden, now known as Ba Đình square, officially creating the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Their success in staging uprisings and in seizing control of most of the country by September 1945 was partially undone, however, by the return of the French a few months later.

Modern period (1945–present)

[edit]First Indochina war (1946–54)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

On 2 September 1945, Hồ Chí Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and held the position of chairman (Chủ Tịch). The rule of communists (under the name of Việt Minh) was cut short, however, by Allied occupation forces who attacked them 21 days later. In 1946, Vietnam (de facto dominated by the communist Viet Minh) had its first National Assembly election, which drafted the first constitution, but the situation was still precarious: the French tried to regain power by force while the non-Communist and Communist forces were engaging each other in sporadic battle. On 6 March 1946, the Viet Minh accepted that their state became a free one within the French Union while Cochinchina remained under French rule.

Hồ's party and its national-front Việt Minh hunted down and executed left-opposition Trotskyists who had a significant presence in Saigon.[140][141] In the interregnum between the surrender of the Japanese occupiers in August 1945 and the British-assisted French reconquest of the city in late September, the "Fourth Internationalists" and other popular groupings—the nationalist VNQDĐ and the syncretic Cao Dai and Hòa Hảo sects—had formed their own militias.[142][143][144] A year later in Paris, asked by Daniel Guerin about the fate of Trotskyist leader Tạ Thu Thâu (executed in September),[145][146] Hồ Chí Minh, while allowing that "Thâu was a great patriot", replied: "All those who do not follow the line which I have laid down will be broken."[147] At his direction, the Việt Minh broke or substantially weakened all rival anti-colonial forces,[148][149] but in the talks in France of 1946 Hồ failed to secure national unity and independence from the French.[150]

In late 1946, after his return from France, the French embarked on a full-scale war against the DRV, initiating what was to become known as the First Indochina War with a naval bombardment of Haiphong that killed over 6000 people.[151] Communist government later attacked France in Hanoi capital, leading to the real war; but the city was finally captured by the French army. As a political alternative to Ho Chi Minh and his DRV, France decided, following his service to the Japanese, to bring back the former emperor Bảo Đại. As part of decolonization after WWII with the pressure of the US and French left, after negotiations, France recognized Vietnam's independence in 1949 and the transfer of autonomous functions and the buildings to the Vietnamese only took place gradually.[152] A Provisional Central Government was formed in 1948, partly reuniting the protectorates of Annam and Tonkin, but the Bảo Đại refused his assent insisting that on a complete reunification of Vietnam. In Saigon, the French had designated the direct-rule colony of Cochinchina as a separate "Autonomous Republic" (Cộng hòa Nam Kỳ).[153] With the Élysée Accords in March 1949 after negotiations between France and native anti-communist politicians, Vietnam regained Cochinchina in June[154] and the State of Vietnam was proclaimed as an independent associated state within the French Union in July, and Bảo Đại became its Head of State.[153] The Élysée Accords was ratified by the French on 2 February 1950, completely abolishing the Treaty of Huế (1884) and French colonial rule in Vietnam. The country was still part of French Indochina. On 4 June 1954, the French government of Prime Minister Joseph Laniel signed the Matignon Accords with the State of Vietnam government of Prime Minister Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Lộc to recognize the complete independence of Vietnam within the French Union. However, the Accords had not yet been ratified by the heads of both countries.[155][156] On 7 September 1954 the French handed the Norodom Palace over to the South Vietnamese government.[157] On 30 December 1954, Indochinese Federation was completely dissolved.

Partition and the Vietnam War (1954–1975)

[edit]

Despite substantial U.S. assistance, the French were persuaded to withdraw from Indochina when in May 1954 the Viet Minh with the help of China from 1950 inflicted a decisive defeat of their forces at Dien Bien Phu. In July 1954, an agreement negotiated at Geneva, signed by the DRV, France, the People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom, provisionally divided Vietnam along the 17th Parallel, with Hồ Chí Minh's communist DRV government ruling the North from Hanoi and Ngô Đình Diệm's State of Vietnam (from 1955, the Republic of Vietnam), governing the South from Saigon. The French withdrew completely from South Vietnam under pressure from the US and South Vietnam in 1956 and in 1960 the last French public property was transferred to South Vietnam.[158] A nation-wide election for a united administration was to be held in July 1956. Diem's regime rejected the agreement, while the United States merely "took note" of the ceasefire agreements and declared that it would "refrain from the threat or use of force to disturb them.[159] Partitition came into force, but the promised elections were never held.

Between 1953 and 1956, the North Vietnamese government instituted various agrarian reforms, including "rent reduction" and "land reform", which resulted in significant political oppression. During the land reform, testimony from North Vietnamese witnesses suggested a ratio of one execution for every 160 village residents, which extrapolated nationwide would indicate nearly 100,000 executions. Because the campaign was concentrated mainly in the Red River Delta area, a lower estimate of 50,000 executions became widely accepted by scholars at the time.[160][161][162][163] However, declassified documents from the Vietnamese and Hungarian archives indicate that the number of executions was much lower than reported at the time, although likely greater than 13,500.[164] In the South, Diem went about crushing political and religious opposition, imprisoning or killing of thousands.[165]