Theory of computation

In theoretical computer science and mathematics, the theory of computation is the branch that deals with what problems can be solved on a model of computation, using an algorithm, how efficiently they can be solved or to what degree (e.g., approximate solutions versus precise ones). The field is divided into three major branches: automata theory and formal languages, computability theory, and computational complexity theory, which are linked by the question: "What are the fundamental capabilities and limitations of computers?".[1]

In order to perform a rigorous study of computation, computer scientists work with a mathematical abstraction of computers called a model of computation. There are several models in use, but the most commonly examined is the Turing machine.[2] Computer scientists study the Turing machine because it is simple to formulate, can be analyzed and used to prove results, and because it represents what many consider the most powerful possible "reasonable" model of computation (see Church–Turing thesis).[3] It might seem that the potentially infinite memory capacity is an unrealizable attribute, but any decidable problem[4] solved by a Turing machine will always require only a finite amount of memory. So in principle, any problem that can be solved (decided) by a Turing machine can be solved by a computer that has a finite amount of memory.

History

[edit]The theory of computation can be considered the creation of models of all kinds in the field of computer science. Therefore, mathematics and logic are used. In the last century, it separated from mathematics and became an independent academic discipline with its own conferences such as FOCS in 1960 and STOC in 1969, and its own awards such as the IMU Abacus Medal (established in 1981 as the Rolf Nevanlinna Prize), the Gödel Prize, established in 1993, and the Knuth Prize, established in 1996.

Some pioneers of the theory of computation were Ramon Llull, Alonzo Church, Kurt Gödel, Alan Turing, Stephen Kleene, Rózsa Péter, John von Neumann and Claude Shannon.

Branches

[edit]Automata theory

[edit]| Grammar | Languages | Automaton | Production rules (constraints) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type-0 | Recursively enumerable | Turing machine | (no restrictions) |

| Type-1 | Context-sensitive | Linear-bounded non-deterministic Turing machine | |

| Type-2 | Context-free | Non-deterministic pushdown automaton | |

| Type-3 | Regular | Finite-state automaton | and |

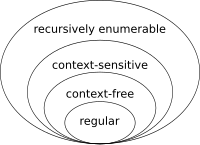

Automata theory is the study of abstract machines (or more appropriately, abstract 'mathematical' machines or systems) and the computational problems that can be solved using these machines. These abstract machines are called automata. Automata comes from the Greek word (Αυτόματα) which means that something is doing something by itself. Automata theory is also closely related to formal language theory,[5] as the automata are often classified by the class of formal languages they are able to recognize. An automaton can be a finite representation of a formal language that may be an infinite set. Automata are used as theoretical models for computing machines, and are used for proofs about computability.

Formal Language theory

[edit]

Language theory is a branch of mathematics concerned with describing languages as a set of operations over an alphabet. It is closely linked with automata theory, as automata are used to generate and recognize formal languages. There are several classes of formal languages, each allowing more complex language specification than the one before it, i.e. Chomsky hierarchy,[6] and each corresponding to a class of automata which recognizes it. Because automata are used as models for computation, formal languages are the preferred mode of specification for any problem that must be computed.

Computability theory

[edit]Computability theory deals primarily with the question of the extent to which a problem is solvable on a computer. The statement that the halting problem cannot be solved by a Turing machine[7] is one of the most important results in computability theory, as it is an example of a concrete problem that is both easy to formulate and impossible to solve using a Turing machine. Much of computability theory builds on the halting problem result.

Another important step in computability theory was Rice's theorem, which states that for all non-trivial properties of partial functions, it is undecidable whether a Turing machine computes a partial function with that property.[8]

Computability theory is closely related to the branch of mathematical logic called recursion theory, which removes the restriction of studying only models of computation which are reducible to the Turing model.[9] Many mathematicians and computational theorists who study recursion theory will refer to it as computability theory.

Computational complexity theory

[edit]

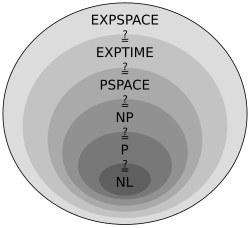

Complexity theory considers not only whether a problem can be solved at all on a computer, but also how efficiently the problem can be solved. Two major aspects are considered: time complexity and space complexity, which are respectively how many steps it takes to perform a computation, and how much memory is required to perform that computation.

In order to analyze how much time and space a given algorithm requires, computer scientists express the time or space required to solve the problem as a function of the size of the input problem. For example, finding a particular number in a long list of numbers becomes harder as the list of numbers grows larger. If we say there are n numbers in the list, then if the list is not sorted or indexed in any way we may have to look at every number in order to find the number we're seeking. We thus say that in order to solve this problem, the computer needs to perform a number of steps that grow linearly in the size of the problem.

To simplify this problem, computer scientists have adopted Big O notation, which allows functions to be compared in a way that ensures that particular aspects of a machine's construction do not need to be considered, but rather only the asymptotic behavior as problems become large. So in our previous example, we might say that the problem requires steps to solve.

Perhaps the most important open problem in all of computer science is the question of whether a certain broad class of problems denoted NP can be solved efficiently. This is discussed further at Complexity classes P and NP, and P versus NP problem is one of the seven Millennium Prize Problems stated by the Clay Mathematics Institute in 2000. The Official Problem Description was given by Turing Award winner Stephen Cook.

Models of computation

[edit]Aside from a Turing machine, other equivalent (See: Church–Turing thesis) models of computation are in use.

- Lambda calculus

- A computation consists of an initial lambda expression (or two if you want to separate the function and its input) plus a finite sequence of lambda terms, each deduced from the preceding term by one application of Beta reduction.

- Combinatory logic

- is a concept which has many similarities to -calculus, but also important differences exist (e.g. fixed point combinator Y has normal form in combinatory logic but not in -calculus). Combinatory logic was developed with great ambitions: understanding the nature of paradoxes, making foundations of mathematics more economic (conceptually), eliminating the notion of variables (thus clarifying their role in mathematics).

- μ-recursive functions

- a computation consists of a mu-recursive function, i.e. its defining sequence, any input value(s) and a sequence of recursive functions appearing in the defining sequence with inputs and outputs. Thus, if in the defining sequence of a recursive function the functions and appear, then terms of the form 'g(5)=7' or 'h(3,2)=10' might appear. Each entry in this sequence needs to be an application of a basic function or follow from the entries above by using composition, primitive recursion or μ recursion. For instance if , then for 'f(5)=3' to appear, terms like 'g(5)=6' and 'h(5,6)=3' must occur above. The computation terminates only if the final term gives the value of the recursive function applied to the inputs.

- Markov algorithm

- a string rewriting system that uses grammar-like rules to operate on strings of symbols.

- Register machine

- is a theoretically interesting idealization of a computer. There are several variants. In most of them, each register can hold a natural number (of unlimited size), and the instructions are simple (and few in number), e.g. only decrementation (combined with conditional jump) and incrementation exist (and halting). The lack of the infinite (or dynamically growing) external store (seen at Turing machines) can be understood by replacing its role with Gödel numbering techniques: the fact that each register holds a natural number allows the possibility of representing a complicated thing (e.g. a sequence, or a matrix etc.) by an appropriately huge natural number — unambiguity of both representation and interpretation can be established by number theoretical foundations of these techniques.

In addition to the general computational models, some simpler computational models are useful for special, restricted applications. Regular expressions, for example, specify string patterns in many contexts, from office productivity software to programming languages. Another formalism mathematically equivalent to regular expressions, finite automata are used in circuit design and in some kinds of problem-solving. Context-free grammars specify programming language syntax. Non-deterministic pushdown automata are another formalism equivalent to context-free grammars. Primitive recursive functions are a defined subclass of the recursive functions.

Different models of computation have the ability to do different tasks. One way to measure the power of a computational model is to study the class of formal languages that the model can generate; in such a way to the Chomsky hierarchy of languages is obtained.

References

[edit]- ^ Sipser (2013, p. 1):

"central areas of the theory of computation: automata, computability, and complexity."

- ^ Hodges, Andrew (2012). Alan Turing: The Enigma (The Centenary ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15564-7.

- ^ Rabin, Michael O. (June 2012). Turing, Church, Gödel, Computability, Complexity and Randomization: A Personal View.

- ^ Donald Monk (1976). Mathematical Logic. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9780387901701.

- ^ Hopcroft, John E. and Jeffrey D. Ullman (2006). Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation. 3rd ed. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-45536-9.

- ^ Chomsky hierarchy (1956). "Three models for the description of language". Information Theory, IRE Transactions on. 2 (3). IEEE: 113–124. doi:10.1109/TIT.1956.1056813. S2CID 19519474.

- ^ Alan Turing (1937). "On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. 2 (42). IEEE: 230–265. doi:10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230. S2CID 73712. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Henry Gordon Rice (1953). "Classes of Recursively Enumerable Sets and Their Decision Problems". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 74 (2). American Mathematical Society: 358–366. doi:10.2307/1990888. JSTOR 1990888.

- ^ Martin Davis (2004). The undecidable: Basic papers on undecidable propositions, unsolvable problems and computable functions (Dover Ed). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486432281.

Further reading

[edit]- Textbooks aimed at computer scientists

(There are many textbooks in this area; this list is by necessity incomplete.)

- Hopcroft, John E.; Motwani, Rajeev; Ullman, Jeffrey D. (2006) [1979]. Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-321-45536-3. — One of the standard references in the field.

- Linz P (2007). An introduction to formal language and automata. Narosa Publishing. ISBN 9788173197819.

- Sipser, Michael (2013). Introduction to the Theory of Computation (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-133-18779-0.

- Eitan Gurari (1989). An Introduction to the Theory of Computation. Computer Science Press. ISBN 0-7167-8182-4. Archived from the original on 2007-01-07.

- Hein, James L. (1996) Theory of Computation. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett. ISBN 978-0-86720-497-1 A gentle introduction to the field, appropriate for second-year undergraduate computer science students.

- Taylor, R. Gregory (1998). Models of Computation and Formal Languages. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510983-2 An unusually readable textbook, appropriate for upper-level undergraduates or beginning graduate students.

- Jon Kleinberg, and Éva Tardos (2006): Algorithm Design, Pearson/Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-32129535-4

- Lewis, F. D. (2007). Essentials of theoretical computer science A textbook covering the topics of formal languages, automata and grammars. The emphasis appears to be on presenting an overview of the results and their applications rather than providing proofs of the results.

- Martin Davis, Ron Sigal, Elaine J. Weyuker, Computability, complexity, and languages: fundamentals of theoretical computer science, 2nd ed., Academic Press, 1994, ISBN 0-12-206382-1. Covers a wider range of topics than most other introductory books, including program semantics and quantification theory. Aimed at graduate students.

- Books on computability theory from the (wider) mathematical perspective

- Hartley Rogers, Jr (1987). Theory of Recursive Functions and Effective Computability, MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-68052-1

- S. Barry Cooper (2004). Computability Theory. Chapman and Hall/CRC. ISBN 1-58488-237-9..

- Carl H. Smith, A recursive introduction to the theory of computation, Springer, 1994, ISBN 0-387-94332-3. A shorter textbook suitable for graduate students in Computer Science.

- Historical perspective

- Richard L. Epstein and Walter A. Carnielli (2000). Computability: Computable Functions, Logic, and the Foundations of Mathematics, with Computability: A Timeline (2nd ed.). Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. ISBN 0-534-54644-7..

External links

[edit]- Theory of Computation at MIT

- Theory of Computation at Harvard

- Computability Logic - A theory of interactive computation. The main web source on this subject.