Nebuchadnezzar II

| Nebuchadnezzar II | |

|---|---|

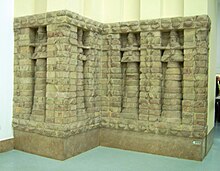

A portion of the so-called "Tower of Babel stele", depicting Nebuchadnezzar II on the right and featuring a depiction of Babylon's great ziggurat (the Etemenanki) on the left[a] | |

| King of the Neo-Babylonian Empire | |

| Reign | August 605 BC – 7 October 562 BC |

| Predecessor | Nabopolassar |

| Successor | Amel-Marduk |

| Born | c. 642 BC[b] Uruk (?) |

| Died | 7 October 562 BC (aged c. 80) Babylon |

| Spouse | Amytis of Babylon (?) |

| Issue Among others | |

| Akkadian | Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

| Dynasty | Babylonian dynasty |

| Father | Nabopolassar |

Nebuchadnezzar II (/ˌnɛbjʊkədˈnɛzər/ NEB-yuu-kəd-NEZ-ər; Babylonian cuneiform: ![]() Nabû-kudurri-uṣur,[6][7][c] meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir";[8] Biblical Hebrew: נְבוּכַדְנֶאצַּר, romanized: Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar),[d] also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II,[8] was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from the death of his father Nabopolassar in 605 BC to his own death in 562 BC. Historically known as Nebuchadnezzar the Great,[9][10] he is typically regarded as the empire's greatest king.[8][11][12] Nebuchadnezzar remains famous for his military campaigns in the Levant, for his construction projects in his capital, Babylon, including the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and for the role he plays in Jewish history.[8] Ruling for 43 years, Nebuchadnezzar was the longest-reigning king of the Babylonian dynasty. By the time of his death, he was among the most powerful rulers in the world.[11]

Nabû-kudurri-uṣur,[6][7][c] meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir";[8] Biblical Hebrew: נְבוּכַדְנֶאצַּר, romanized: Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar),[d] also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II,[8] was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from the death of his father Nabopolassar in 605 BC to his own death in 562 BC. Historically known as Nebuchadnezzar the Great,[9][10] he is typically regarded as the empire's greatest king.[8][11][12] Nebuchadnezzar remains famous for his military campaigns in the Levant, for his construction projects in his capital, Babylon, including the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and for the role he plays in Jewish history.[8] Ruling for 43 years, Nebuchadnezzar was the longest-reigning king of the Babylonian dynasty. By the time of his death, he was among the most powerful rulers in the world.[11]

Possibly named after his grandfather of the same name, or after Nebuchadnezzar I (r. c. 1125–1104 BC), one of Babylon's greatest ancient warrior-kings, Nebuchadnezzar II had already secured renown for himself during his father's reign, leading armies in the Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire. At the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC, Nebuchadnezzar inflicted a crushing defeat on an Egyptian army led by Pharaoh Necho II, and ensured that the Neo-Babylonian Empire would succeed the Neo-Assyrian Empire as the dominant power in the ancient Near East. Shortly after this victory, Nabopolassar died and Nebuchadnezzar became king.

Despite his successful military career during his father's reign, the first third or so of Nebuchadnezzar's reign saw little to no major military achievements, and notably a disastrous failure in an attempted invasion of Egypt. These years of lackluster military performance saw some of Babylon's vassals, particularly in the Levant, beginning to doubt Babylon's power, viewing the Neo-Babylonian Empire as a paper tiger rather than a power truly on the level of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The situation grew so severe that people in Babylonia itself began disobeying the king, some going as far as to revolt against Nebuchadnezzar's rule.[citation needed]

After this disappointing early period as king, Nebuchadnezzar's luck turned. In the 580s BC, Nebuchadnezzar engaged in a successful string of military actions in the Levant against the vassal states in rebellion there, likely with the ultimate intent of curbing Egyptian influence in the region. In 587 BC, Nebuchadnezzar destroyed the Kingdom of Judah and its capital, Jerusalem. The destruction of Jerusalem led to the Babylonian captivity as the city's population, and people from the surrounding lands, were deported to Babylonia. The Jews thereafter referred to Nebuchadnezzar, the greatest enemy they had faced until that point, as a "destroyer of nations" (משחית גוים, Jer. 4:7). The biblical Book of Jeremiah paints Nebuchadnezzar as a cruel enemy but also as God's appointed ruler of the world and a divine instrument to punish disobedience. Through the destruction of Jerusalem, the capture of the rebellious Phoenician city of Tyre, and other campaigns in the Levant, Nebuchadnezzar completed the Neo-Babylonian Empire's transformation into the new great power of the ancient Near East.

In addition to his military campaigns, Nebuchadnezzar is remembered as a great builder king. The prosperity ensured by his wars allowed Nebuchadnezzar to conduct great building projects in Babylon, and elsewhere in Mesopotamia. The modern image of Babylon is largely of the city as it was after Nebuchadnezzar's projects, during which among other works he rebuilt many of the city's religious buildings, including the Esagila and Etemenanki, renovated its existing palace, constructed a brand-new palace, and beautified its ceremonial centre through renovations to the city's Processional Street and the Ishtar Gate. As most of Nebuchadnezzar's inscriptions deal with his building projects rather than military accomplishments, he was for a time seen by historians mostly as a builder rather than a warrior.

Sources

[edit]There are very few cuneiform sources for the period between 594 BC and 557 BC, which covers much of the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II and the reigns of his three immediate successors, Amel-Marduk, Neriglissar and Labashi-Marduk.[13] This lack of sources has the unfortunate effect that even though Nebuchadnezzar had the longest reign of all of them, less is confidently known of Nebuchadnezzar's reign than of the reigns of almost all the other Neo-Babylonian kings. Though the handful of cuneiform sources recovered, notably the Babylonian Chronicle, confirm some events of his reign, such as conflicts with the Kingdom of Judah, other events, such as the 586 BC destruction of Solomon's Temple and other military campaigns Nebuchadnezzar possibly conducted, are not covered in any known cuneiform documents.[14]

As a result, historical reconstructions of this period generally follow secondary sources in Hebrew, Greek and Latin to determine what events transpired at the time, in addition to contract tablets from Babylonia.[13] Though use of the sources written by later authors, many of them created several centuries after Nebuchadnezzar's time and often reflecting their own cultural attitudes to the events and figures discussed,[15] presents problems in and of itself, blurring the line between history and tradition, it is the only possible approach to gain insight into Nebuchadnezzar's reign.[14]

Background

[edit]Name

[edit]

Nebuchadnezzar II's name in Akkadian was Nabû-kudurri-uṣur,[6] meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir".[8] The name was often interpreted in earlier scholarship as "Nabu, protect the boundary", given that the word kudurru can also mean 'boundary' or 'line'. Modern historians support the 'heir' interpretation over the 'boundary' interpretation in terms of this name. There is no reason to believe that the Babylonians intended the name to be difficult to interpret or to have a double meaning.[16]

Nabû-kudurri-uṣur is typically anglicised to 'Nebuchadnezzar', following how the name is most commonly rendered in Hebrew and Greek, particularly in most of the Bible. In Hebrew, the name was rendered as נְבוּכַדְנֶאצַּר (Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar) and in Greek it was rendered as Ναβουχοδονόσορ (Nabouchodonosor). Some scholars, such as Donald Wiseman, prefer the anglicisation "Nebuchadrezzar", with an "r" rather than an "n", following the assumption that "Nebuchadnezzar" is a later, corrupted form of the contemporary Nabû-kudurri-uṣur.[17]

The alternative anglicisation "Nebuchadrezzar" derives from how the name is rendered in the books of Jeremiah and Ezekiel, נְבוּכַדְרֶאצַּר (Nəḇūḵaḏreʾṣṣar), a more faithful transliteration of the original Akkadian name. The Assyriologist Adrianus van Selms suggested in 1974 that the variant with an "n" rather than an "r" was a rude nickname, deriving from an Akkadian rendition like Nabû-kūdanu-uṣur, which means 'Nabu, protect the mule', though there is no concrete evidence for this idea. Van Selms believed that a nickname like that could derive from Nebuchadnezzar's early reign, which was plagued by political instability.[17]

Nebuchadnezzar II's name, Nabû-kudurri-uṣur, was identical to the name of his distant predecessor, Nebuchadnezzar I (r. c. 1125–1104 BC), who ruled more than five centuries before Nebuchadnezzar II's time.[6] Like Nebuchadnezzar II, Nebuchadnezzar I was a renowned warrior-king who appeared in a time of political upheaval and defeated the forces of Babylon's enemies, in Nebuchadnezzar I's case the Elamites.[18] Although theophoric names using the god Nabu are common in texts from the early Neo-Babylonian Empire, the name Nebuchadnezzar is relatively rare, being mentioned only four times with certainty. Though there is no evidence that Nabopolassar named his son after Nebuchadnezzar I, Nabopolassar was knowledgeable in history and actively worked to connect his rule to the rule of the Akkadian Empire, which preceded him by nearly two thousand years. The significance of his son and heir bearing the name of one of Babylon's greatest kings would not have been lost on Nabopolassar.[19]

If Jursa's theory concerning Nabopolassar's origin is correct, it is alternatively possible that Nebuchadnezzar II was named after his grandfather of the same name, as the Babylonians employed patronymics, rather than after the previous king.[19][20]

Ancestry and early life

[edit]

Nebuchadnezzar was the eldest son of Nabopolassar (r. 626–605 BC), the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This is confirmed by Nabopolassar's inscriptions, which explicitly name Nebuchadnezzar as his "eldest son", as well as inscriptions from Nebuchadnezzar's reign, which refer to him as the "first" or "chief son" of Nabopolassar, and as Nabopolassar's "true" or "legitimate heir".[21] The Neo-Babylonian Empire was founded through Nabopolassar's rebellion, and later war, against the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which liberated Babylonia after nearly a century of Assyrian control. The war resulted in the complete destruction of Assyria,[22] and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which rose in its place, was powerful, but hastily built and politically unstable.[23]

As Nabopolassar never clarified his ancestry in lineage in any of his inscriptions, his origin is not entirely clear. Subsequent historians have variously identified Nabopolassar as a Chaldean,[24][25][26] an Assyrian[27] or a Babylonian.[28] Although no evidence conclusively confirms him as being of Chaldean origin, the term "Chaldean dynasty" is frequently used by modern historians for the royal family he founded, and the term "Chaldean Empire" remains in use as an alternate historiographical name for the Neo-Babylonian Empire.[24]

Nabopolassar appears to, regardless of his ethnic origin, have been strongly connected to the city of Uruk,[26][29] located south of Babylon. It is possible that he was a member of its ruling elite before becoming king[26] and there is a growing body of evidence that Nabopolassar's family originated in Uruk, for instance that Nebuchadnezzar's daughters lived in the city.[30]

In 2007, Michael Jursa advanced the theory that Nabopolassar was a member of a prominent political family in Uruk, whose members are attested since the reign of Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC). To support his theory, Jursa pointed to how documents describe how the grave and body of "Kudurru", a deceased governor of Uruk, was desecrated due to the anti-Assyrian activities of Kudurru's two sons, Nabu-shumu-ukin and a son whose name is mostly missing. The desecration went so far as to drag Kudurru's body through the streets of Uruk. Kudurru can be identified with Nebuchadnezzar (Nabû-kudurri-uṣur, "Kudurru" simply being a common and shortened nickname), a prominent official in Uruk who served as its governor under the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BC) in the 640s BC.[2]

In Assyrian tradition, the desecration of a dead body showed that the deceased individual and their surviving family were traitors and enemies of the state, and that they had to be completely eradicated, serving to punish them even after death. The name of the son whose name is unpreserved in the letter ended with either ahi, nâsir or uṣur, and the remaining traces can fit with the name Nabû-apla-uṣur, meaning that Nabopolassar could be the other son mentioned in the letter and thus a son of Kudurru.[2]

Strengthening this connection is that Nebuchadnezzar II is attested very early during his father's reign, from 626/625 to 617 BC, as high priest of the Eanna temple in Uruk, where he is often attested under the nickname "Kudurru".[2][3] Nebuchadnezzar must have been made high priest at a very young age, considering that his year of death, 562 BC, is 64 years after 626 BC.[4] The original Kudurru's second son, Nabu-shumu-ukin, also appears to be attested as a prominent general under Nabopolassar, and the name was also used by Nebuchadnezzar II for one of his sons, possibly honoring his dead uncle.[2]

Nebuchadnezzar as crown prince

[edit]

Nebuchadnezzar's military career began in the reign of his father, though little information survives. Based on a letter sent to the temple administration of the Eanna temple, it appears that Nebuchadnezzar participated in his father's campaign to take the city of Harran in 610 BC.[31] Harran was the seat of Ashur-uballit II, who had rallied what remained of the Assyrian army and ruled the Neo-Assyrian rump state.[32] The Babylonian victory in the Harran campaign and the defeat of Ashur-uballit in 609 BCE marked the end of the ancient Assyrian monarchy, which would never be restored.[33] According to the Babylonian Chronicles, Nebuchadnezzar also commanded an army in an unspecified mountainous region for several months in 607 BC.[31]

In the war against the Babylonians and Medes, Assyria had allied with Pharaoh Psamtik I of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, who had been interested in ensuring Assyria's survival so that Assyria could remain as a buffer state between his own kingdom and the Babylonian and Median kingdoms.[34] After the fall of Harran, Psamtik's successor, Pharaoh Necho II, personally led a large army into former Assyrian lands to turn the tide of the war and restore the Neo-Assyrian Empire,[35] even though it was more or less a lost cause as Assyria had already collapsed.[36] As Nabopolassar was occupied with fighting Urartu in the north, the Egyptians took control of the Levant largely unopposed, capturing territories as far north as the city of Carchemish in Syria, where Necho established his base of operations.[37]

Nebuchadnezzar's greatest victory from his time as crown prince came at the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC,[31] which put an end to Necho's campaign in the Levant by inflicting a crushing defeat on the Egyptians.[38][36] Nebuchadnezzar had been the sole commander of the Babylonian army at this battle as his father had chosen to stay in Babylon,[22] perhaps on account of illness.[37] Necho's forces were completely annihilated by Nebuchadnezzar's army, with Babylonian sources claiming that not a single Egyptian escaped alive.[39] The account of the battle in the Babylonian Chronicle reads as follows:[31]

The king of Akkad[e] stayed home (while) Nebuchadnezzar, his eldest son (and) crown prince mustered [the army of Akkad]. He took his army's lead and marched to Carchemish, which is on the bank of the Euphrates. He crossed the river at Carchemish. [...] They did battle together. The army of Egypt retreated before him. He inflicted a [defeat] upon them (and) finished them off completely. In the district of Hamath the army of Akkad overtook the remainder of the army of [Egypt which] managed to escape [from] the defeat and which was not overcome. They inflicted a defeat upon them (so that) a single (Egyptian) man [did not return] home. At that time Nebuchadnezzar conquered all of Ha[ma]th.[31]

The story of Nebuchadnezzar's victory at Carchemish reverberated through history, appearing in many later ancient accounts, including in the Book of Jeremiah and the Books of Kings in the Bible. It is possible to conclude, based on subsequent geopolitics, that the victory resulted in all of Syria and Israel coming under the control of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, a feat which the Assyrians under Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BC) only accomplished after five years of protracted military campaigns.[31] The defeat of Egypt at Carchemish ensured that the Neo-Babylonian Empire would grow to become the major power of the ancient Near East, and the uncontested successor of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[22][41]

Reign

[edit]Accession to the throne

[edit]

Nabopolassar died just a few weeks after Nebuchadnezzar's victory at Carchemish.[31] At this point in time, Nebuchadnezzar was still away on his campaign against the Egyptians,[39] having chased the retreating Egyptian forces to the region around the city of Hamath.[42] The news of Nabopolassar's death reached Nebuchadnezzar's camp on 8 Abu (late July),[42][43] and Nebuchadnezzar quickly arranged affairs with the Egyptians and rushed back to Babylon,[39] where he was proclaimed king on 1 Ulūlu (mid-August).[42]

The speed in which Nebuchadnezzar returned to Babylon might be due to the threat that one of his brothers (two are known by name: Nabu-shum-lishir[44][45] and Nabu-zer-ushabshi)[46] could claim the throne in his absence. Though Nebuchadnezzar had been recognised as the eldest son and heir by Nabopolassar, Nabu-shum-lishir,[44] Nabopolassar's second-born son,[45] had been recognised as "his equal brother", a dangerously vague title.[44][f] Despite these possible fears, there were no attempts made at usurping his throne at this time.[44]

One of Nebuchadnezzar's first acts as king was to bury his father. Nabopolassar was laid in a huge coffin, adorned with ornamented gold plates and fine dresses with golden beads, which was then placed within a small palace he had constructed in Babylon.[44] Shortly thereafter, before the end of the month in which he had been crowned, Nebuchadnezzar returned to Syria to resume his campaign. The Babylonian Chronicle records that "he marched about victoriously", meaning that he faced little to no resistance, returning to Babylon after several months of campaigning.[42] The Syrian campaign, though it resulted in a certain amount of plunder, was not a complete success in that it did not ensure Nebuchadnezzar's grasp on the region. He had seemingly failed to inspire fear, given that none of the westernmost states in the Levant swore fealty to him and paid tribute.[12]

Early military campaigns

[edit]Though little information survives concerning them, the Babylonian Chronicle preserves brief accounts of Nebuchadnezzar's military activities in his first eleven years as king. In 604 BC, Nebuchadnezzar campaigned in the Levant once again, conquering the city of Ascalon.[42] According to the Babylonian Chronicle, Ascalon's king was captured and taken to Babylon, and the city was plundered and levelled to the ground. Modern excavations at Ascalon have confirmed that the city was more or less destroyed at this point in time.[48] The Ascalon campaign was preceded by a campaign in Syria, which was more successful than Nebuchadnezzar's first, resulting in oaths of fealty from the rulers of Phoenicia.[12]

In 603 BC, Nebuchadnezzar campaigned in a land whose name is not preserved in the surviving copy of the chronicle. The chronicle records that this campaign was extensive, given that the account mentions the construction of large siege towers and a siege of a city, the name of which does not survive either. Anson Rainey speculated in 1975 that the city taken was Gaza, whereas Nadav Na'aman thought in 1992 that it was Kummuh in south-eastern Anatolia. In the second half of the 5th century BC, some documents mentioned the towns Isqalanu (the name derived from Ascalon) and Hazzatu (the name possibly derived from Gaza) near the city of Nippur, indicating that deportees from both of these cities lived near Nippur, and as such possibly that they had been captured at around the same time.[42]

In both 602 BC and 601 BC, Nebuchadnezzar campaigned in the Levant, though little information survives beyond that a "vast" amount of booty was brought from the Levant to Babylonia in 602 BC.[42] On account of the entry for 602 BC also referring to Nabu-shum-lishir, Nebuchadnezzar's younger brother, in a fragmentary and unclear context, it is possible that Nabu-shum-lishir led a revolt against his brother in an attempt to usurp the throne in that year, especially since he is no longer mentioned in any sources after 602 BC.[49] The damage to the text however makes this idea speculative and conjectural.[42]

In the 601 BC campaign, Nebuchadnezzar departed from the Levant and then marched into Egypt. Despite the defeat at Carchemish in 605 BC, Egypt still had a great amount of influence in the Levant, even though the region was ostensibly under Babylonian rule. Thus, a campaign against Egypt was logical in order to assert Babylonian dominance, and also carried enormous economic and propagandistic benefits, but it was also risky and ambitious. The path into Egypt was difficult, and the lack of secure control of either side of the Sinai Desert could spell disaster.[50]

Nebuchadnezzar's invasion of Egypt failed – the Babylonian Chronicle states that both the Egyptian and Babylonian armies suffered a huge number of casualties.[50] Though Egypt was not conquered, the campaign did result in momentarily curbing Egyptian interest in the Levant, given that Necho II gave up his ambitions in the region.[51] In 599 BC, Nebuchadnezzar marched his army into the Levant and then attacked and raided the Arabs in the Syrian desert. Though apparently successful, it is unclear what the achievements gained in this campaign were.[50]

In 598 BC, Nebuchadnezzar campaigned against the Kingdom of Judah, succeeding in capturing the city of Jerusalem.[52] Judah represented a prime target of Babylonian attention given that it was at the epicenter of competition between Babylon and Egypt. By 601 BC, Judah's king, Jehoiakim, had begun to openly challenge Babylonian authority, counting on that Egypt would lend support to his cause. Nebuchadnezzar's first, 598–597 BC, assault on Jerusalem is recorded in the Bible, but also in the Babylonian Chronicle,[48] which describes it as follows:[48]

The seventh year [of Nebuchadnezzar], in the month of Kislimu, the king of Akkad mustered his troops, marched to the Levant, and set up quarters facing the city of Judah [Jerusalem]. In the month of Addaru [early in 597 BC], the second day, he took the city and captured the king. He installed there a king of his choice. He colle[cted] its massive tribute and went back to Babylon.[48]

Jehoiakim had died during Nebuchadnezzar's siege and been replaced by his son, Jeconiah, who was captured and taken to Babylon, with his uncle Zedekiah installed in his place as king of Judah. Jeconiah is recorded as being alive in Babylonia thereafter, with records as late as 592 or 591 BC listing him among the recipients of food at Nebuchadnezzar's palace and still referring to him as the 'king of the land of Judah'.[48]

In 597 BC, the Babylonian army departed for the Levant again, but appears to not have engaged in any military activities as they turned back immediately after reaching the Euphrates. The following year, Nebuchadnezzar marched his army along the Tigris river to do battle with the Elamites, but no actual battle happened as the Elamites retreated out of fear once Nebuchadnezzar was a day's march away. In 595 BC, Nebuchadnezzar stayed at home in Babylon but soon had to face a rebellion against his rule there, though he defeated the rebels, with the chronicle stating that the king "put his large army to the sword and conquered his foe." Shortly thereafter, Nebuchadnezzar again campaigned in the Levant and secured large amounts of tribute. In the last year recorded in the chronicle, 594 BC, Nebuchadnezzar campaigned in the Levant yet again.[52]

There were several years without any noteworthy military activity at all. Notably, Nebuchadnezzar spent all of 600 BC in Babylon, when the chronicle excuses the king by stating that he stayed in Babylon to "refit his numerous horses and chariotry". Some of the years when Nebuchadnezzar was victorious can also hardly be considered real challenges. Raiding the Arabs in 599 BC was not a major military accomplishment and the victory over Judah and the retreat of the Elamites were not secured on the battlefield. It thus appears that Nebuchadnezzar achieved little military success after the failure of his invasion of Egypt. Nebuchadnezzar's poor military record had dangerous geopolitical consequences. According to the Bible, in Zedekiah's fourth year as king of Judah (594 BC), the kings of Ammon, Edom, Moab, Sidon and Tyre met in Jerusalem to deal with the possibility of throwing off Babylonian control.[53]

Evidence that Babylonian control was beginning to unravel is also clear from contemporary Babylonian records, such as the aforementioned rebellion in Babylonia itself, as well as records of a man being executed in 594 BC at Borspippa for "breaking his oath to the king". The oath-breaking was serious enough that the judge in the trial was Nebuchadnezzar himself. It is also possible that Babylonian–Median relations were becoming strained, with records of a "Median defector" being housed in Nebuchadnezzar's palace and some inscriptions indicating that the Medes were beginning to be seen as "enemies". By 594 BC, the failure of the Egyptian invasion, and the lacklustre state of Nebuchadnezzar's other campaigns, loomed high. According to the Assyriologist Israel Ephʿal, Babylon at this time was seen by its contemporaries more like a "paper tiger" (i. e. an ineffectual threat) than a great empire, like Assyria just a few decades prior.[54]

Destruction of Jerusalem

[edit]

From his appointment as king of Judah, Zedekiah waited for the opportune moment to throw off Babylonian control. After Pharaoh Necho II's death in 595 BC, Egyptian intervention in affairs in the Levant increased once again under his successors, Psamtik II (r. 595–589 BC) and Apries (r. 589–570 BC), who both worked to encourage anti-Babylonian rebellions.[48] It is possible that the Babylonian failure to invade Egypt in 601 BC helped inspire revolts against the Babylonian Empire.[55] The outcome of these efforts was Zedekiah's open revolt against Nebuchadnezzar's authority.[48] Unfortunately, no cuneiform sources are preserved from this time and the only known account of the fall of Judah is the biblical account.[48][56]

In 589 BC, Zedekiah refused to pay tribute to Nebuchadnezzar, and he was closely followed in this by Ithobaal III, the king of Tyre.[57] In 587 BC, Ammon, Edom and Moab likewise rebelled.[58] In response to Zedekiah's uprising,[48] Nebuchadnezzar conquered and destroyed the Kingdom of Judah in 586 BC,[48][56] one of the great achievements of his reign.[48][56] The campaign, which probably ended in the summer of 586 BC, resulted in the plunder and destruction of the city of Jerusalem, a permanent end to Judah, and it led to the Babylonian captivity, as the Jews were captured and deported to Babylonia.[48] Archaeological excavations confirm that Jerusalem and the surrounding area was destroyed and depopulated. It is possible that the intensity of the destruction carried out by Nebuchadnezzar at Jerusalem and elsewhere in the Levant was due to the implementation of something akin to a scorched earth-policy, aimed at stopping Egypt from gaining a foothold there.[59]

Some Jewish administration was allowed to remain in the region under the governor Gedaliah, governing from Mizpah under close Babylonian monitoring.[48] According to the Bible, and the 1st-century AD Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, Zedekiah attempted to flee after resisting the Babylonians, but was captured at Jericho and suffered a terrible fate. According to the narrative, Nebuchadnezzar wanted to make an example out of him given that Zedekiah was not an ordinary vassal, but a vassal directly appointed by Nebuchadnezzar. As such, Zedekiah was supposedly taken to Riblah in northern Syria, where he had to watch his sons being executed before having his eyes gouged out and sent to be imprisoned in Babylon.[60]

Per the Books of Kings in the Bible, the campaign against Judah was longer than typical Mesopotamian wars, with the siege of Jerusalem lasting 18–30 months (depending on the calculation), rather than the typical length of less than a year. Whether the unusual length of the siege indicates that the Babylonian army was weak, unable to break into the city for more than a year, or that Nebuchadnezzar by this time had succeeded in stabilising his rule in Babylonia and could thus wage war patiently without being pressured by time to escalate the siege, is not certain.[56]

Later military campaigns

[edit]

It is possible that the Egyptians took advantage of the Babylonians being preoccupied with besieging Jerusalem. Herodotus describes Pharaoh Apries as campaigning in the Levant, taking the city of Sidon and fighting the Tyrians, which indicates a renewed Egyptian invasion of the Levant.[57] Apries is unlikely to have been as successful as Herodotus describes, given that it is unclear how the Egyptian navy would have defeated the superior navies of the Phoenician cities, and even if some cities had been taken, they must have shortly thereafter fallen into Babylonian hands again.[60] Tyre had rebelled against Nebuchadnezzar at around the same time as Judah, and Nebuchadnezzar moved to retake the city after his successful subduing of the Jews.[60]

The biblical Book of Ezekiel describes Tyre in 571 BC as if it had been recently captured by the Babylonian army.[61] The supposed length of the siege, 13 years,[62] is only given by Flavius Josephus, and is subject to debate among modern scholars.[59] Josephus's account of Nebuchadnezzar's reign is obviously not entirely historic, as he describes Nebuchadnezzar as, five years after the destruction of Jerusalem, invading Egypt, capturing the Pharaoh and appointing another Pharaoh in his place.[56] A stele from Tahpanhes uncovered in 2011 records that Nebuchadnezzar attempted to invade Egypt in 582 BC, although Apries' forces managed to repel the invasion.[63]

Josephus states that Nebuchadnezzar besieged Tyre in the seventh year of "his" reign, though it is unclear whether "his" in this context refers to Nebuchadnezzar or to Ithobaal III of Tyre. If it refers to Nebuchadnezzar, a siege begun in 598 BC and lasting for thirteen years, later simultaneously with the siege of Jerusalem, is unlikely to have gone unmentioned in Babylonian records. If the seventh year of Ithobaal is intended, the beginning of the siege may conjecturally be placed after Jerusalem's fall. If the siege lasting 13 years is taken at face value, the siege would then not have ended before 573 or 572 BC.[62] The supposed length of the siege can be ascribed to the difficulty in besieging the city: Tyre was located on an island 800 metres from the coast, and could not be taken without naval support. Though the city withstood numerous sieges, it would not be captured until Alexander the Great's siege in 332 BC.[64]

In the end, the siege was resolved without a need of battle and did not result in the Tyre being conquered.[59][64] It seems Tyre's king and Nebuchadnezzar came to an agreement for Tyre to continue to be ruled by vassal kings, though probably under heavier Babylonian control than before. Documents from Tyre near the end of Nebuchadnezzar's reign demonstrate that the city had become a centre for Babylonian military affairs in the region.[59] According to later Jewish tradition, it is possible that Ithobaal III was deposed and taken as a prisoner to Babylon, with another king, Baal II, proclaimed by Nebuchadnezzar in his place.[65]

It is possible that Nebuchadnezzar campaigned against Egypt in 568 BC,[66][67] given that a fragmentary Babylonian inscription, given the modern designation BM 33041, from that year records the word "Egypt" as well as possibly traces of the name "Amasis" (the name of the then incumbent Pharaoh, Amasis II, r. 570–526 BC). A stele of Amasis, also fragmentary, may also describe a combined naval and land attack by the Babylonians. Recent evidence suggests that the Babylonians were initially successful during the invasion and gained a foothold in Egypt, but they were repelled by Amasis' forces.[68] If Nebuchadnezzar did campaign against Egypt again, he was unsuccessful again, given that Egypt did not come under Babylonian rule.[66]

Nebuchadnezzar's campaigns in the Levant, most notably those directed towards Jerusalem and Tyre, completed the Neo-Babylonian Empire's transformation from a rump state of the Neo-Assyrian Empire to the new dominant power of the ancient Near East.[59] Still, Nebuchadnezzar's military accomplishments can be questioned,[12] given that the borders of his empire, by the end of his reign, had not noticeably increased in size and that he had not managed to conquer Egypt. Even after a reign of several decades, Nebuchadnezzar's greatest victory remained his victory over the Egyptians at Carchemish in 605 BC, before he even became king.[69]

Building projects

[edit]

The Babylonian king was traditionally a builder and restorer, and as such large-scale building projects were important as a legitimizing factor for Babylonian rulers.[70] Nebuchadnezzar extensively expanded and rebuilt his capital city of Babylon and the most modern historical and archaeological interpretations of the city reflect it as it appeared after Nebuchadnezzar's construction projects.[59] The projects were made possible through the prospering economy during Nebuchadnezzar's reign, sustained by his conquests.[71] His building inscriptions record work done to numerous temples, notably the restoration of the Esagila, the main temple of Babylon's national deity Marduk, and the completion of the Etemenanki, a great ziggurat dedicated to Marduk.[59]

Extensive work was also conducted on civil and military structures. Among the most impressive efforts was the work done surrounding the city's northern ceremonial entrance, the Ishtar Gate. These projects included restoration work on the South Palace, inside the city walls, the construction of a completely new North Palace, on the other side of the walls facing the gate, as well as the restoration of Babylon's Processional Street, which led through the gate, and of the gate itself.[71] The ruins of Nebuchadnezzar's North Palace are poorly preserved and as such its structure and appearance are not entirely understood. Nebuchadnezzar also constructed a third palace, the Summer Palace, built some distance north of the inner city walls in the northernmost corner of the outer walls.[72]

The restored Ishtar Gate was decorated with blue and yellow glazed bricks and depictions of bulls (symbols of the god Adad) and dragons (symbols of the god Marduk). Similar bricks were used for the walls surrounding the Processional Street, which also featured depictions of lions (symbols of the goddess Ishtar).[71] Babylon's Processional Street, the only such street yet excavated in Mesopotamia, ran along the eastern walls of the South Palace and exited the inner city walls at the Ishtar Gate, running past the North Palace. To the south, this street went by the Etemenanki, turning to the west and going over a bridge constructed either under the reign of Nabopolassar or Nebuchadnezzar.[73]

Some of the bricks of the Processional Street bear the name of the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC) on their underside, perhaps indicating that construction of the street had begun already during his reign, but the fact that the upper side of the bricks all bear the name of Nebuchadnezzar suggests that construction of the street was completed under Nebuchadnezzar's reign.[73] Glazed bricks such as the ones used in the Procession Street were also used in the throne room of the South Palace, which was decorated with depictions of lions and tall, stylized palm trees.[71]

Nebuchadnezzar also directed building efforts on the city of Borsippa, with several of his inscriptions recording restoration work on that city's temple, the Ezida, dedicated to the god Nabu. Additionally, Nebuchadnezzar also restored the ziggurat of the Ezida, the E-urme-imin-anki, and also worked on the temple of Gula, Etila, as well as numerous other temples and shrines in the city. Nebuchadnezzar also repaired Borsippa's walls.[74]

Other great building projects by Nebuchadnezzar include the Nar-Shamash, a canal to bring water from the Euphrates close to the city of Sippar, and the Median Wall, a large defensive structure built to defend Babylonia against incursions from the north.[75] The Median Wall was one of two walls built to protect Babylonia's northern border. Further evidence that Nebuchadnezzar believed the north to be the most likely point of attack for his enemies comes from that he fortified the walls of northern cities, such as Babylon, Borsippa and Kish, but left the walls of southern cities, such as Ur and Uruk, as they were.[76] Nebuchadnezzar also began work on the Royal Canal, also known as Nebuchadnezzar's Canal, a great canal linking the Euphrates to the Tigris which in time completely transformed the agriculture of the region, but the structure was not completed until the reign of Nabonidus, who ruled as the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire from 556 to 539 BC.[75]

Death and succession

[edit]Nebuchadnezzar died at Babylon in 562 BC.[11] The last known tablet dated to Nebuchadnezzar's reign, from Uruk, is dated to the same day, 7 October, as the first known tablet of his successor, Amel-Marduk, from Sippar.[77] Amel-Marduk's administrative duties probably began before he became king, during the last few weeks or months of his father's reign when Nebuchadnezzar was ill and dying.[78] Having ruled for 43 years, Nebuchadnezzar's reign was the longest of his dynasty[18] and he would be remembered favourably by the Babylonians.[79]

Amel-Marduk's accession does not appear to have gone smoothly.[80] Amel-Marduk was not the eldest living son of Nebuchadnezzar and the reason why he was picked as crown prince is not known.[81][82] The choice is especially strange given that some sources suggest that the relationship between Nebuchadnezzar and Amel-Marduk was particularly poor, with one surviving text describing both as parties in some form of conspiracy and accusing one of them (the text is too fragmentary to determine which one) of failing in the most important duties of Babylonian kingship through exploiting Babylon's populace and desecrating its temples.[81] Amel-Marduk also at one point appears to have been imprisoned by his father, possibly on account of the Babylonian aristocracy having proclaimed him as king while Nebuchadnezzar was away.[78] It is possible that Nebuchadnezzar intended to replace Amel-Marduk as heir with another son, but died before doing so.[83]

In one of Nebuchadnezzar's late inscriptions, written more than forty years into his reign, he wrote that he had been chosen for the kingship by the gods before he was even born. Mesopotamian rulers typically only stressed divine legitimacy in this fashion when their actual legitimacy was questionable, a method often employed by usurpers. Given that Nebuchadnezzar at this point had been king for several decades and was the legitimate heir of his predecessor, the inscription is very strange, unless it was intended to help legitimize Nebuchadnezzar's successor, Amel-Marduk, who as a younger son and a former conspirator could be seen as politically problematic.[80]

Family and children

[edit]

No surviving contemporary Babylonian documents provide the name of Nebuchadnezzar's wife. According to Berossus, her name was Amytis, daughter of Astyages, king of the Medes. Berossus writes that '[Nabopolassar] sent troops to the assistance of Astyages, the tribal chieftain and satrap of the Medes in order to obtain a daughter of Astyages, Amyitis, as wife for his son [Nebuchadnezzar]'. Though the ancient Greek historian Ctesias instead wrote that Amytis was the name of a daughter of Astyages who had married Cyrus I of Persia, it seems more likely that a Median princess would marry a member of the Babylonian royal family, considering the good relations established between the two during Nabopolassar's reign.[46]

Given that Astyages was still too young during Nabopolassar's reign to already have children, and was not yet king, it seems more probable that Amytis was Astyages's sister, and thus a daughter of his predecessor, Cyaxares.[84] By marrying his son to a daughter of Cyaxares, Nebuchadnezzar's father Nabopolassar likely sought to seal the alliance between the Babylonians and the Medes.[85]

According to tradition, Nebuchadnezzar constructed the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, featuring exotic shrubs, vines and trees as well as artificial hills, watercourses and knolls, so that Amytis would feel less homesick for the mountains of Media. No archaeological evidence for these gardens has yet been found.[86]

Nebuchadnezzar had six known sons.[87] Most of the sons,[88] with the exceptions of Marduk-nadin-ahi[82] and Eanna-sharra-usur,[89] are attested very late in their father's reign. It is possible that they might have been the product of a second marriage and that they could have been born relatively late in Nebuchadnezzar's reign, possibly after his known daughters.[88] The known sons of Nebuchadnezzar are:

- Marduk-nadin-ahi (Akkadian: Marduk-nādin-aḫi)[88] – the earliest attested of Nebuchadnezzar's children, attested in a legal document, probably as an adult as he is described as being in charge of his own land, already in Nebuchadnezzar's third year as king (602/601 BC). Presumably Nebuchadnezzar's firstborn son, if not eldest child, and thus his legitimate heir.[90] He is also attested very late in Nebuchadnezzar's reign, named as a "royal prince" in a document recording the purchase of dates by Sin-mār-šarri-uṣur, his servant, in 563 BC.[89][82]

- Eanna-sharra-usur (Akkadian: Eanna-šarra-uṣur)[89] – named as a "royal prince" among sixteen people in a document at Uruk from 587 BC recorded as receiving barley "for the sick".[89]

- Amel-Marduk (Akkadian: Amēl-Marduk),[78] originally named Nabu-shum-ukin (Nabû-šum-ukīn)[78] – succeeded Nebuchadnezzar as king in 562 BC. His reign was marred with intrigues and he only ruled for two years before being murdered and usurped by his brother-in-law, Neriglissar. Later Babylonian sources mostly speak ill of his reign.[87][91] Amel-Marduk is first attested, notably as crown prince, in a document 566 BC.[92] Given that Amel-Marduk had an older brother in Marduk-nadin-ahi, alive as late as 563 BC, why he was named crown prince is not clear.[93]

- Marduk-shum-usur (Akkadian: Marduk-šum-uṣur[88] or Marduk-šuma-uṣur)[89] – named as a "royal prince" in documents from Nebuchadnezzar's 564 BC and 562 BC years, recording payments by his scribe to the Ebabbar temple in Sippar.[89]

- Mushezib-Marduk (Akkadian: Mušēzib-Marduk)[88] – named as a "royal prince" once in a contract tablet from 563 BC.[89]

- Marduk-nadin-shumi (Akkadian: Marduk-nādin-šumi)[89] – named as a "royal prince" once in a contract tablet from 563 BC.[89]

Three of Nebuchadnezzar's daughters are known by name:[30]

- Kashshaya (Akkadian: Kaššaya)[94] – attested in several economic documents from Nebuchadnezzar's reign as "the king's daughter".[95] Her name is of unclear origin; it might be derived from the word kaššû (kassite).[96] Kashshaya is attested from contemporary texts as a resident of (and landowner in) Uruk.[30] Kashshaya is typically, although speculatively, identified as the daughter of Nebuchadnezzar who married Neriglissar.[88][97]

- Innin-etirat (Akkadian: Innin-ēṭirat)[98] – attested as "the king's daughter" in a 564 BC document which records her granting mār-banûtu status[98] ("status of a free man")[99] to a slave by the name Nabû-mukkê-elip.[98] The document in question was written at Babylon, but names including the divine prefix Innin are almost unique to Uruk, suggesting that she was a resident of that city.[30]

- Ba'u-asitu (Akkadian: Ba'u-asītu)[98] – attested as the owner of a piece of real estate in an economic document. The precise reading and meaning of her name is somewhat unclear. Paul-Alain Beaulieu, who in 1998 published the translated text which confirms her existence, believes that her name is best interpreted as meaning "Ba'u is a/the physician".[100] The document was written at Uruk, where Ba'u-asitu is presumed to have lived.[30]

It is possible that one of Nebuchadnezzar's daughters married the high official Nabonidus,[101] although there is no evidence for this.[102] Marriage to a daughter of Nebuchadnezzar could explain how Nabonidus could become king, and also explain why certain later traditions, such as the Book of Daniel in the Bible, describe Nabonidus's son, Belshazzar, as Nebuchadnezzar's son (descendant).[101][103] Alternatively, these later traditions might instead derive from royal propaganda.[104]

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus names the "last great queen" of the Babylonian Empire as "Nitocris", though that name, nor any other name, is not attested in contemporary Babylonian sources. Herodotus's description of Nitocris contains a wealth of legendary material that makes it difficult to determine whether he uses the name to refer to Nabonidus's wife or mother. In 1982, William H. Shea proposed that Nitocris may tentatively be identified as the name of Nabonidus's wife and Belshazzar's mother.[105]

Legacy

[edit]Assessment by historians

[edit]Because of the scarcity of sources, assessment by historians of Nebuchadnezzar's character and the nature of his reign have differed considerably over time.[106] He has typically been regarded as the greatest and most prestigious king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.[8][11][12]

Since military activity was not a major issue described in the inscriptions of any Neo-Babylonian king regardless of their actual military accomplishments, in sharp contrast to the inscriptions of their Neo-Assyrian predecessors, Nebuchadnezzar's own inscriptions record very little about his wars. Out of the fifty or so known inscriptions by the king, only a single one deals with military action, and in this case only small-scale conflicts in the Lebanon region. Many Assyriologists, such as Wolfram von Soden in 1954, thus initially assumed that Nebuchadnezzar had mainly been a builder-king, devoting his energy and efforts to building and restoring his country.[106]

A major change in evaluations of Nebuchadnezzar came with the publication of the tablets of the Babylonian Chronicle by Donald Wiseman in 1956, which cover the geopolitical events of Nebuchadnezzar's first eleven years as king. From the publication of these tablets and onwards, historians have shifted to perceiving Nebuchadnezzar as a great warrior, devoting special attention to the military achievements of his reign.[106]

According to the historian Josette Elayi, writing in 2018, Nebuchadnezzar is somewhat difficult to characterise on account of the scarcity of Babylonian source material. Elayi wrote, about Nebuchadnezzar, that "[h]e was a conqueror, even though reservations can be had about his military capabilities. There was no lack of statesmanlike qualities, given his success in building the Babylonian Empire. He was a great builder, who restored a country that for a long time had been devastated by war. That is roughly all we know about him because the Babylonian Chronicles and other texts say little about his personality."[12]

In Jewish and biblical tradition

[edit]

The Babylonian captivity initiated by Nebuchadnezzar came to an end with the fall of Babylon to the Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great in 539 BC. Within a year of their liberation, some exiled Jews returned to their homeland. Their liberation did little to erase the memory of five decades of imprisonment and oppression. Instead, Jewish literary accounts ensured that accounts of the hardship endured by the Jews, as well as of the monarch responsible for it, would be remembered for all time.[6] The Book of Jeremiah calls Nebuchadnezzar a "lion" and a "destroyer of nations".[107]

Nebuchadnezzar's story thus found its way into the Old Testament of the Bible.[6] The Bible narrates how Nebuchadnezzar destroyed the Kingdom of Judah, besieged, plundered and destroyed Jerusalem, and how he took away the Jews in captivity, portraying him as a cruel enemy of the Jewish people.[108] The Bible also portrays Nebuchadnezzar as the legitimate ruler of all the nations of the world, appointed to rule the world by God. As such, Judah, through divine ruling, should have obeyed Nebuchadnezzar and should not have rebelled. Nebuchadnezzar is also depicted as carrying out death sentences pronounced by God, slaying two false prophets. Nebuchadnezzar's campaigns of conquest against other nations are portrayed as being in-line with God's will for Nebuchadnezzar's dominance.[109]

Despite Nebuchadnezzar's negative portrayal, the Book of Jeremiah notably refers to him using the epithet 'my servant' (i.e. God's servant) in three passages:

- Nebuchadnezzar's attack on the Kingdom of Judah is theologically justified in the Book of Jeremiah on account of Judah's populace's disobedience of God, and the king is called "Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon, my servant".

- The Book of Jeremiah also states that God has made all the Earth and given it to whom it seemed proper to give it to, deciding upon giving all of the lands of the world to "Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon, my servant".

- The Book of Jeremiah also prophesies Nebuchadnezzar's victory over Egypt, stating that "Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon, my servant" will invade Egypt and "deliver to death those appointed for death, and to captivity those appointed for captivity, and to the sword those appointed for the sword".

Given that Nebuchadnezzar was the enemy of what the Bible proclaims as God's chosen people, possibly the worst enemy they had faced until this point, there must be a special reason for referring to him with the epithet "my servant". Other uses of this epithet are usually limited to some of the most positively portrayed figures, such as the various prophets, Jacob (the symbol of the chosen people) and David (the chosen king). Klaas A. D. Smelik noted in 2004 that "in the Hebrew Bible, there is no better company conceivable than these; at the same time, there is no candidate less likely for this title of honour than the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar".[110]

It is possible that the epithet is a later addition, as it is missing in the Septuagint version of the Old Testament, perhaps added after Nebuchadnezzar began to be seen in a slightly more favourable light than immediately after Jerusalem's destruction.[111] Alternatively, possible theological explanations include Nebuchadnezzar being seen, despite his cruelty, as an instrument in fulfilling God's universal plan; or perhaps that designating him as a "servant" of God was to show that readers should not fear Nebuchadnezzar, but his true master, God.[112]

In the Book of Daniel, widely considered by scholars to be a work of historical fiction,[113][114][115][116] the figure of Nebuchadnezzar differs considerably from his portrayal in the Book of Jeremiah. He is for the most part depicted as a merciless and despotic ruler. The king has a nightmare, and asks his wise men, including Daniel and his three companions Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, to interpret the dream, but refuses to state the dream's contents. When the servants protest, Nebuchadnezzar sentences all of them, including Daniel and his companions, to death.[117]

By the end of the story, when Daniel has successfully interpreted the dream, Nebuchadnezzar shows much gratitude, showering Daniel with gifts, appointing him the governor of the "province of Babylon" and making him the chief of the kingdom's wise men. A second story again casts Nebuchadnezzar as a tyrannical and pagan king, who, after Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego refuse to worship a newly erected golden statue, sentences them to death through being thrown into a fiery furnace. They are miraculously delivered, and Nebuchadnezzar then acknowledges God as the "lord of kings" and "god of gods".[117]

Though Nebuchadnezzar is also mentioned as acknowledging the Hebrews' God as the true god in other passages of the Book of Daniel, it is apparent that his supposed conversion to Judaism does not change his violent character, given that he proclaims that anyone who speaks amiss of God "shall be cut in pieces and their houses shall be made a dunghill". In a third story, Daniel interprets another dream as meaning that Nebuchadnezzar will lose his mind and live like an animal for seven years before being restored to his normal state (Daniel 1-4).[117] The Nebuchadnezzar in the Book of Daniel, a fickle tyrant who is not particularly consistent in his faith, contrasts with the typical "servant of God" in other books of the Bible.[118]

Given that Nebuchadnezzar is referred to as the father of Belshazzar in the Book of Daniel, it is probable that this portrayal of Nebuchadnezzar, especially the story of his madness, was actually based on Belshazzar's actual father, Nabonidus, the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (r. 556–539 BC). Separate Jewish and Hellenistic traditions exist concerning Nabonidus having been mad,[119] and it is likely that this madness was simply reattributed to Nebuchadnezzar in the Book of Daniel through conflation.[120][121]

Some later traditions conflated Nebuchadnezzar with other rulers as well, such as the Assyrian Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BC), the Persian Artaxerxes III (r. 358–338 BC), the Seleucids Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175–164 BC) and Demetrius I Soter (r. 161–150 BC) and the Armenian Tigranes the Great (r. 95–55 BC).[122] The apocryphal Book of Judith, which probably applies the name "Nebuchadnezzar" to Tigranes the Great of Armenia, refers to Nebuchadnezzar as a "king of the Assyrians", rather than of the Babylonians, and demonstrates that Nebuchadnezzar was still viewed as an evil king, responsible for destroying Jerusalem, looting its temple, taking the Jews hostage in Babylon, and for the various misdeeds ascribed to him in later Jewish writings.[123]

Other

[edit]Nebuchadnezzar is referred to as Buḫt Nuṣṣur (بخت نصر) in works of the mediaeval scholar al-Ṭabarī, where he is credited with conquering Egypt, Syria, Phoenicia and Arabia. The historical Nebuchadnezzar never conquered Egypt, and it appears that al-Ṭabarī transferred to him the achievements of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 681–669).[124] In similar fashion Strabo, citing Megasthenes, mentioned in a list of mythical and semi-legendary conquerors, a Nabocodrosor as having led an army to the Pillars of Hercules and being revered by the Chaldaeans.[125]

Titles

[edit]In most of his inscriptions, Nebuchadnezzar is typically only titled as "Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, son of Nabopolassar, king of Babylon" or "Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, the one who provides for Esagil and Ezida, son of Nabopolassar, king of Babylon".[126] In economic documents, Nebuchadnezzar is also ascribed the ancient title "king of the Universe",[127] and he sometimes also used the title "king of Sumer and Akkad", used by all the Neo-Babylonian kings.[128] Some inscriptions accord Nebuchadnezzar more elaborate version of his titles, including the following variant, attested in an inscription from Babylon:[126]

Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, pious prince, the favorite of the god Marduk, exalted ruler who is the beloved of the god Nabû, the one who deliberates (and) acquires wisdom, the one who constantly seeks out the ways of their divinity (and) reveres their dominion, the indefatigable governor who is mindful of provisioning Esagil and Ezida daily and (who) constantly seeks out good things for Babylon and Borsippa, the wise (and) pious one who provides for Esagil and Ezida, foremost heir of Nabopolassar, king of Babylon, am I.[126]

See also

[edit]- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

- Nebuchadnezzar (Blake) – famous 19th-century painting depicting the biblical story of Nebuchadnezzar's madness

- Nabucco – 19th-century opera by Giuseppe Verdi based loosely on the biblical story of Nebuchadnezzar

Notes

[edit]- ^ As the inscriptions on the stele were written by Nebuchadnezzar, he is also unquestionably the king depicted. The stele is one of only four known certain contemporary depictions of Nebuchadnezzar, with the other three being carved depictions on cliff-faces in Lebanon, in much poorer condition than the depiction in the stele. The Etemenanki ziggurat was presumably the inspiration for the Biblical Tower of Babel, hence the name 'Tower of Babel stele'.[1]

- ^ Nebuchadnezzar was made high priest of the Eanna temple in Uruk by his father in 626/625 BC.[2][3] It is assumed that he was made high priest at a very young age, considering his death taking place more than sixty years later.[4] It is not known at what age Babylonians became eligible for priesthood, but there are records of freshly initiated Babylonian priests aged 15 or 16.[5]

- ^ The cuneiform signs are AG.NÍG.DU-ÙRU

- ^ This is the Hebrew spelling in 13 cases; in 13 other cases, the Hebrew spelling is one of the following:

- נְבֻכַדְנֶאצַּר, Nəḇuḵaḏneʾṣṣar − with בֻ ḇu instead of בוּ ḇū, in 2 Kings 24:1, 24:10, 25:1, 25:8, 1 Chronicles 5:41 (a.k.a. 6:15), and Jeremiah 28:11 and 28:14;

- נְבוּכַדְנֶצַּר, Nəḇūḵaḏneṣṣar – without א ʾ (like the usual Aramaic spelling), in Ezra 1:7 and Nehemiah 7:6;

- נְבֻכַדְנֶצַּר, Nəḇuḵaḏneṣṣar – with בֻ instead of בוּ and without א (like the Aramaic spelling used in Daniel 3:14, 5:11, and 5:18), in Daniel 1:18 and 2:1;

- נְבוּכַדְנֶצּוֹר, Nəḇūḵaḏneṣṣōr – without א and with צּוֹ (ṣ)ṣō instead of צַּ (ṣ)ṣa, in Ezra 2:1;

- נְבוּכַדנֶאצַּר, Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar – without the shva quiescens, in Jeremiah 28:3, and Ester 2:6.

- ^ "Akkad" here refers to Babylonia[40] and derives from the city Akkad, the capital of the ancient Akkadian Empire that Nabopolassar worked to connect himself to.[19] The "king of Akkad" referred to here is thus Nabopolassar.[31]

- ^ The word translated as 'equal brother', talīmu, has also been alternatively translated as 'chosen brother', 'close brother' or 'beloved brother'. Regardless of the correct interpretation, the epithet clearly illustrates Nabopolassar's great affection for his second son. Such public affection bestowed upon the brother of the heir to the throne many times led to later conflicts and usurpations.[47]

References

[edit]- ^ George 2011, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b c d e Jursa 2007, pp. 127–134.

- ^ a b Popova 2015, p. 402.

- ^ a b Popova 2015, p. 403.

- ^ Waerzeggers & Jursa 2008, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Sack 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Porten, Zadok & Pearce 2016, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f Saggs 1998.

- ^ Wallis Budge 1884, p. 116.

- ^ Sack 2004, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d Mark 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Elayi 2018, p. 190.

- ^ a b Sack 1978, p. 129.

- ^ a b Sack 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Sack 2004, p. x.

- ^ Wiseman 1983, p. 3.

- ^ a b Wiseman 1983, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Sack 2004, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Nielsen 2015, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Jursa 2007, pp. 127–133.

- ^ Wiseman 1983, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Sack 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Beaulieu 1989, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Beaulieu 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Johnston 1901, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Bedford 2016, p. 56.

- ^ The British Museum 1908, p. 10.

- ^ Melville 2011, p. 16.

- ^ Da Riva 2017, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d e Beaulieu 1998, p. 198.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ephʿal 2003, p. 179.

- ^ Melville 2011, p. 20.

- ^ Radner 2019, p. 141.

- ^ Lipschits 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Rowton 1951, p. 128.

- ^ a b Sack 2004, p. 7.

- ^ a b Wiseman 1991, p. 182.

- ^ Lipschits 2005, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Wiseman 1991, p. 230.

- ^ Da Riva 2017, p. 77.

- ^ Wiseman 1991, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ephʿal 2003, p. 180.

- ^ Parker & Dubberstein 1942, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Olmstead 1925, p. 35.

- ^ a b Wiseman 1983, p. 7.

- ^ a b Wiseman 1983, p. 8.

- ^ Ayali-Darshan 2012, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Beaulieu 2018, p. 228.

- ^ Da Riva 2013, p. 198.

- ^ a b c Ephʿal 2003, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 191.

- ^ a b Ephʿal 2003, p. 181.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: Jeremiah 27:1-7 - New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ Ephʿal 2003, pp. 181–183.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 192.

- ^ a b c d e Ephʿal 2003, p. 183.

- ^ a b Elayi 2018, p. 195.

- ^ al-Nahar, Maysoun (11 June 2014). "The Iron Age and the Persian Period (1200–332 BC)". In Ababsa, Myriam (ed.). Atlas of Jordan. Contemporain publications. Presses de l'Ifpo. pp. 126–130. ISBN 9782351594384. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Beaulieu 2018, p. 229.

- ^ a b c Elayi 2018, p. 196.

- ^ Ephʿal 2003, p. 184.

- ^ a b Ephʿal 2003, p. 186.

- ^ Kahn 2018, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Ephʿal 2003, p. 187.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 200.

- ^ a b Ephʿal 2003, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 201.

- ^ Kahn 2018, pp. 77.

- ^ Ephʿal 2003, p. 189.

- ^ Porter 1993, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Beaulieu 2018, p. 230.

- ^ Baker 2012, p. 924.

- ^ a b Baker 2012, p. 925.

- ^ Beaulieu 2018, pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b Beaulieu 2018, p. 232.

- ^ Baker 2012, p. 926.

- ^ Parker & Dubberstein 1942, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Weiershäuser & Novotny 2020, p. 1.

- ^ Nielsen 2015, p. 63.

- ^ a b Ayali-Darshan 2012, p. 26.

- ^ a b Ayali-Darshan 2012, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Abraham 2012, p. 124.

- ^ Ayali-Darshan 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Lendering 1995.

- ^ Wiseman 1991, p. 229.

- ^ Polinger Foster 1998, p. 322.

- ^ a b Wiseman 1983, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b c d e f Beaulieu 1998, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wiseman 1983, p. 10.

- ^ Abraham 2012, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Beaulieu 1998, p. 199.

- ^ Popova 2015, p. 405.

- ^ Abraham 2012, p. 125.

- ^ Beaulieu 1998, p. 173.

- ^ Beaulieu 1998, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Beaulieu 1998, p. 181.

- ^ Wiseman 1991, p. 241.

- ^ a b c d Beaulieu 1998, p. 174.

- ^ Botta 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Beaulieu 1998, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Wiseman 1983, p. 11.

- ^ Collins 1993, p. 32.

- ^ Wiseman 1991, p. 244.

- ^ Chavalas 2000, p. 164.

- ^ Shea 1982, pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b c Ephʿal 2003, p. 178.

- ^ Shapiro 1982, p. 328.

- ^ Smelik 2014, p. 110.

- ^ Smelik 2014, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Smelik 2014, pp. 110–12.

- ^ Smelik 2014, pp. 118–20.

- ^ Smelik 2014, p. 133.

- ^ Laughlin 1990, p. 95.

- ^ Seow 2003, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Collins 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Redditt 2008, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Smelik 2014, pp. 127–29.

- ^ Smelik 2014, p. 129.

- ^ Sack 1983, p. 63.

- ^ Beaulieu 2007, p. 137.

- ^ Henze 1999, p. 63.

- ^ Boccaccini 2012, p. 56.

- ^ Boccaccini 2012, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Retsö, Jan (2013). The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads. London, UK; New York City, US: Routledge. pp. 187–89. ISBN 978-1-136-87289-1 – via Archive.

- ^ Strabo, Geography, 15.1.6

- ^ a b c Babylonian royal inscriptions.

- ^ Stevens 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Da Riva 2013, p. 72.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abraham, Kathleen (2012). "A Unique Bilingual and Biliteral Artifact from the Time of Nebuchadnezzar II in the Moussaieff Private Collection". In Lubetski, Meir; Lubetski, Edith (eds.). New Inscriptions and Seals Relating to the Biblical World. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1589835566.

- Ayali-Darshan, Noga (2012). "A Redundancy in Nebuchadnezzar 15 and Its Literary Historical Significance". JANES. 32: 21–29.

- Baker, Heather D. (2012). "The Neo-Babylonian Empire". In Potts, D. T. (ed.). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 914–930. doi:10.1002/9781444360790.ch49. ISBN 9781405189880.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1989). Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon (556-539 BC). Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2250wnt. ISBN 9780300043143. JSTOR j.ctt2250wnt. OCLC 20391775.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1998). "Ba'u-asītu and Kaššaya, Daughters of Nebuchadnezzar II". Orientalia. 67 (2): 173–201. JSTOR 43076387.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2007). "Nabonidus the Mad King: A Reconsideration of His Steles from Harran and Babylon". In Heinz, Marlies; Feldman, Marian H. (eds.). Representations of Political Power: Case Histories from Times of Change and Dissolving Order in the Ancient Near East. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575061351.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2016). "Neo-Babylonian (Chaldean) Empire". The Encyclopedia of Empire. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe220. ISBN 978-1118455074.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2018). A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75. Pondicherry: Wiley. ISBN 978-1405188999.

- Bedford, Peter R. (2016). "Assyria's Demise as Recompense: A Note on Narratives of Resistance in Babylonia and Judah". In Collins, John J.; Manning, J. G. (eds.). Revolt and Resistance in the Ancient Classical World and the Near East: In the Crucible of Empire. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004330184.

- Boccaccini, Gabriele (2012). "Tigranes the Great as "Nebuchadnezzar" in the Book of Judith". In Xeravits, Géza G. (ed.). A Pious Seductress: Studies in the Book of Judith. Göttingen: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110279986.

- Botta, Alejandro F. (2009). The Aramaic and Egyptian Legal Traditions at Elephantine: An Egyptological Approach. T&T Clark International. ISBN 978-0567045331.

- Chavalas, Mark W. (2000). "Belshazzar". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-9053565032.

- Collins, John J. (1993). Cross, Frank Moore (ed.). Daniel: A commentary on the Book of Daniel. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvb936s4. ISBN 0-8006-6040-4. JSTOR j.ctvb936s4.

- Collins, John J. (2002). "Current Issues in the Study of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron (eds.). The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. Vol. I. BRILL. ISBN 978-0391041271.

- Elayi, Josette (2018). The History of Phoenicia. Lockwood Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11wjrh. ISBN 978-1937040819. JSTOR j.ctv11wjrh. S2CID 198105413.

- Ephʿal, Israel (2003). "Nebuchadnezzar the Warrior: Remarks on his Military Achievements". Israel Exploration Journal. 53 (2): 178–191. JSTOR 27927044.

- Da Riva, Rocio (2013). "Nebuchadnezzar II's Prism (EŞ 7834): A New Edition". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie. 103 (2): 196–229. doi:10.1515/za-2013-0005. S2CID 163482606.

- Da Riva, Rocio (2017). "The Figure of Nabopolassar in Late Achaemenid and Hellenistic Historiographic Tradition: BM 34793 and CUA 90". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 76 (1): 75–92. doi:10.1086/690464. S2CID 222433095.

- George, Andrew R. (2011). "A Stele of Nebuchadnezzar II". CUSAS. 17: 153–169.

- Henze, Matthias (1999). The Madness of King Nebuchadnezzar: The Ancient Near Eastern Origins and Early History of Interpretation of Daniel 4. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-9004114210.

- Johnston, Christopher (1901). "The Fall of Nineveh". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 22: 20–22. doi:10.2307/592409. JSTOR 592409.

- Jursa, Michael (2007). "Die Söhne Kudurrus und die Herkunft der neubabylonischen Dynastie" [The Sons of Kudurru and the Origins of the New Babylonian Dynasty]. Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale (in German). 101 (1): 125–136. doi:10.3917/assy.101.0125.

- Kahn, Dan’el (2018). "Nebuchadnezzar and Egypt: An Update on the Egyptian Monuments". Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel. 7 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1628/hebai-2018-0005. S2CID 188600999.

- Laughlin, John C. (1990). "Belshazzar". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

- Lipschits, Oled (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah under Babylonian Rule. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060958.

- Melville, Sarah C. (2011). "The Last Campaign: the Assyrian Way of War and the Collapse of the Empire". In Lee, Wayne E. (ed.). Warfare and Culture in World History. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0814752784.

- Nielsen, John P. (2015). ""I Overwhelmed the King of Elam": Remembering Nebuchadnezzar I in Persian Babylonia". In Silverman, Jason M.; Waerzeggers, Caroline (eds.). Political Memory in and After the Persian Empire. SBL Press. ISBN 978-0884140894.

- Novotny, Jamie; Weiershäuser, Frauke (2024). The Royal Inscriptions of Nabopolassar (625-605 BC) and Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BC), Kings of Babylon, Part 1. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-64602-296-0.

- Olmstead, A. T. (1925). "The Chaldaean Dynasty". Hebrew Union College Annual. 2: 29–55. JSTOR 23502505.

- Parker, Richard A.; Dubberstein, Waldo H. (1942). Babylonian Chronology 626 B.C. – A.D. 45 (PDF). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. OCLC 2600410.

- Polinger Foster, Karen (1998). "Gardens of Eden: Exotic Flora and Fauna in the Ancient Near East" (PDF). Yale F&ES Bulletin. 1998: 320–329. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2006.

- Popova, Olga (2015). "The Royal Family and its Territorial Implantation during the Neo-Babylonian Period". KASKAL. 12 (12): 401–410. doi:10.1400/239747.

- Porten, Bezalel; Zadok, Ran; Pearce, Laurie (2016). "Akkadian Names in Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 375 (375): 1–12. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.375.0001. JSTOR 10.5615/bullamerschoorie.375.0001. S2CID 163575000.

- Porter, Barbara N. (1993). Images, Power, and Politics: Figurative Aspects of Esarhaddon's Babylonian Policy. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 9780871692085.

- Radner, Karen (2019). "Last Emperor or Crown Prince Forever? Aššur-uballiṭ II of Assyria according to Archival Sources". State Archives of Assyria Studies. 28: 135–142.

- Redditt, Paul L. (2008). Introduction to the Prophets. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2896-5.

- Rowton, M. B. (1951). "Jeremiah and the Death of Josiah". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 2 (10): 128–130. doi:10.1086/371028. S2CID 162308322.

- Sack, Ronald H. (1978). "Nergal-šarra-uṣur, King of Babylon as seen in the Cuneiform, Greek, Latin and Hebrew Sources". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie. 68 (1): 129–149. doi:10.1515/zava.1978.68.1.129. S2CID 161101482.

- Sack, Ronald H. (1983). "The Nabonidus Legend". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 77 (1): 59–67. JSTOR 23282496.

- Sack, Ronald H. (2004). Images of Nebuchadnezzar: The Emergence of a Legend (2nd Revised and Expanded ed.). Selinsgrove: Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 1-57591-079-9.

- Seow, C.L. (2003). Daniel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256753.

- Shapiro, David S. (1982). "The Seven Questions of Amos". Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought. 20 (4): 327–331. JSTOR 23260505.

- Shea, William H. (1982). "Nabonidus, Belshazzar, and the Book of Daniel: an Update". Andrews University Seminary Studies. 20 (2): 133–149.

- Smelik, Klaas A. D. (2014). "My Servant Nebuchadnezzar: The Use of the Epithet "My Servant" for the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar in the Book of Jeremiah". Vetus Testamentum. 64 (1): 109–134. doi:10.1163/15685330-12301142. JSTOR 43894101.

- Stevens, Kahtryn (2014). "The Antiochus Cylinder, Babylonian Scholarship and Seleucid Imperial Ideology" (PDF). The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 134: 66–88. doi:10.1017/S0075426914000068. JSTOR 43286072.

- The British Museum (1908). A Guide to the Babylonian and Assyrian Antiquities. London: British Museum. OCLC 70331064.

- Waerzeggers, Caroline; Jursa, Michael (2008). "On the Initiation of Babylonian Priests". Zeitschrift für Altorientalische und Biblische Rechtsgeschichte. 14: 1–38.

- Wallis Budge, Ernest Alfred (1884). Babylonian Life and History. London: Religious Tract Society. OCLC 3165864.

- Weiershäuser, Frauke; Novotny, Jamie (2020). The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon (PDF). Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1646021079.

- Wiseman, Donald J. (1983). Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon: The Schweich Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197261002.

- Wiseman, Donald J. (2003) [1991]. "Babylonia 605–539 B.C.". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: III Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22717-8.

Web sources

[edit]- "Inscriptions by Babylonian kings". Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Lendering, Jona (1995). "Cyaxares". Livius. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2018). "Nebuchadnezzar II". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Saggs, Henry W. F. (1998). "Nebuchadnezzar II". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.